Introduction

The NHS workforce is in crisis – there are currently not enough people with the right skills to provide the high-quality care that the population needs and expects.

Healthcare professionals currently working within the NHS are exhausted and burnt out as a result of working in conditions that are not conducive to providing excellent care. At the time of writing, unresolved industrial action is affecting several disciplines. The NHS is losing considerable numbers of staff with many leaving healthcare entirely or choosing to take up higher-paid positions in other countries. The end result is that patients are waiting longer for treatment only to receive a level of care that is inferior to what they would expect and to what their clinicians would wish to provide. As older people are the biggest user group of health and social care, they are the group who are most frequently affected by delays in access to care and suboptimal experience of care.

This crisis will not be fixed by short term measures that address just one part of the problem. To provide high-quality healthcare for all people in the UK, when and where they need it, requires strategic, system-wide workforce planning and investment in creative and sustainable workforce solutions. This includes improving terms and conditions for NHS and social care staff in order to make health and social care attractive career options and to be able to recruit and retain more staff at all levels. Action on terms and conditions should be complemented by workforce education and development so that more of our current and future workforce have the right skills to care for the biggest group using health and care services: older people. However, central to the solution must be recruiting more people. The British Geriatrics Society (BGS) stands with many other organisations in making the case for more health and care staff. We believe that concerted action to recruit and train more people with the skills required for a rapidly ageing population is central to having a sustainable workforce that is fit for the future. In this paper, we take that argument one step further in putting a number on how many more geriatricians are needed to work in the NHS to meet the needs of an ageing population with increasingly complex needs.

We believe that concerted action to recruit and train more people with the skills required for a rapidly ageing population is central to having a sustainable workforce that is fit for the future.

Care for older people is largely delivered by multidisciplinary teams, whether in acute, community or primary care. However, these teams need the leadership of geriatricians, who are expert in balancing the harms and benefits of interventions for older people with complex needs as a result of frailty and multiple conditions. Therefore, recruitment of geriatricians is only one part of a wider capacity challenge, but it is a vital one to address as part of a strategic approach to workforce planning.

This paper is intended to start the conversation about the workforce needed to provide high-quality care for the ageing population with increasingly complex needs. The paper explains why training, recruiting and retaining geriatricians should be a priority, estimates how many geriatricians are needed to provide safe and effective care for older people, and outlines some of the structural barriers that currently prevent recruitment. The document concludes with six calls for Governments across the UK. There are limitations to this paper, which we acknowledge. However, it is clear that national and local strategic workforce plans must address the need for more geriatricians alongside investment in multidisciplinary teams and in upskilling the entire workforce to care for older people with frailty.

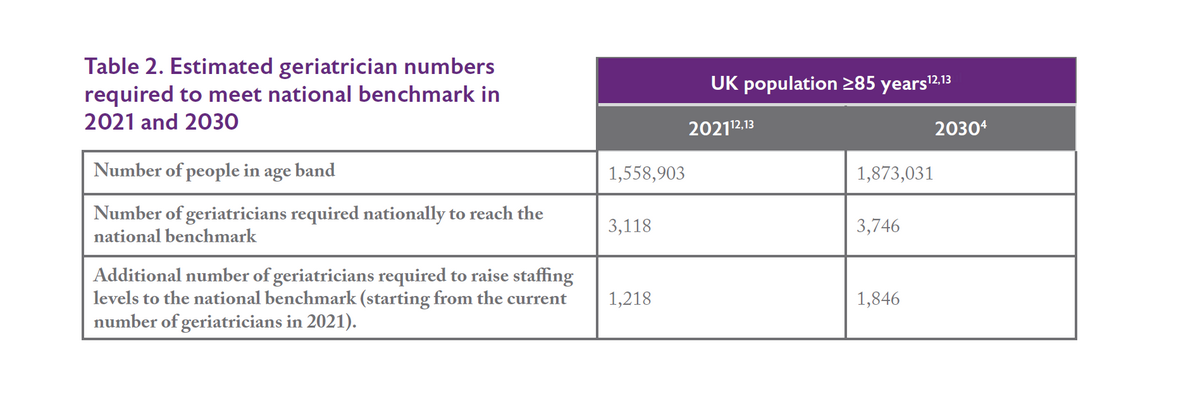

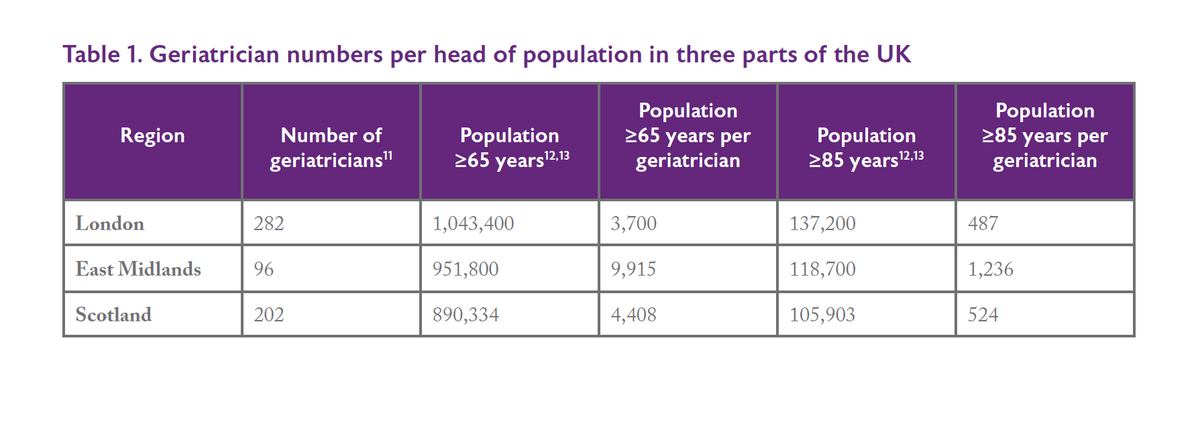

We appreciate that these do not provide perfect comparisons as these areas have different populations and they do not take into consideration the complexities of covering rural and remote locations. However, the figures do provide a starting point and reflect our discussions with the BGS membership. In London we have seen rapid expansion of specialist front-door frailty, surgical liaison, orthogeriatric and community services. Scotland has been a pioneer in the Hospital at Home movement and other models of care in the community. Colleagues in the East Midlands, meanwhile, report feeling overwhelmed and unable to keep pace with the demand for service expansion in both acute and community settings.

We appreciate that these do not provide perfect comparisons as these areas have different populations and they do not take into consideration the complexities of covering rural and remote locations. However, the figures do provide a starting point and reflect our discussions with the BGS membership. In London we have seen rapid expansion of specialist front-door frailty, surgical liaison, orthogeriatric and community services. Scotland has been a pioneer in the Hospital at Home movement and other models of care in the community. Colleagues in the East Midlands, meanwhile, report feeling overwhelmed and unable to keep pace with the demand for service expansion in both acute and community settings.