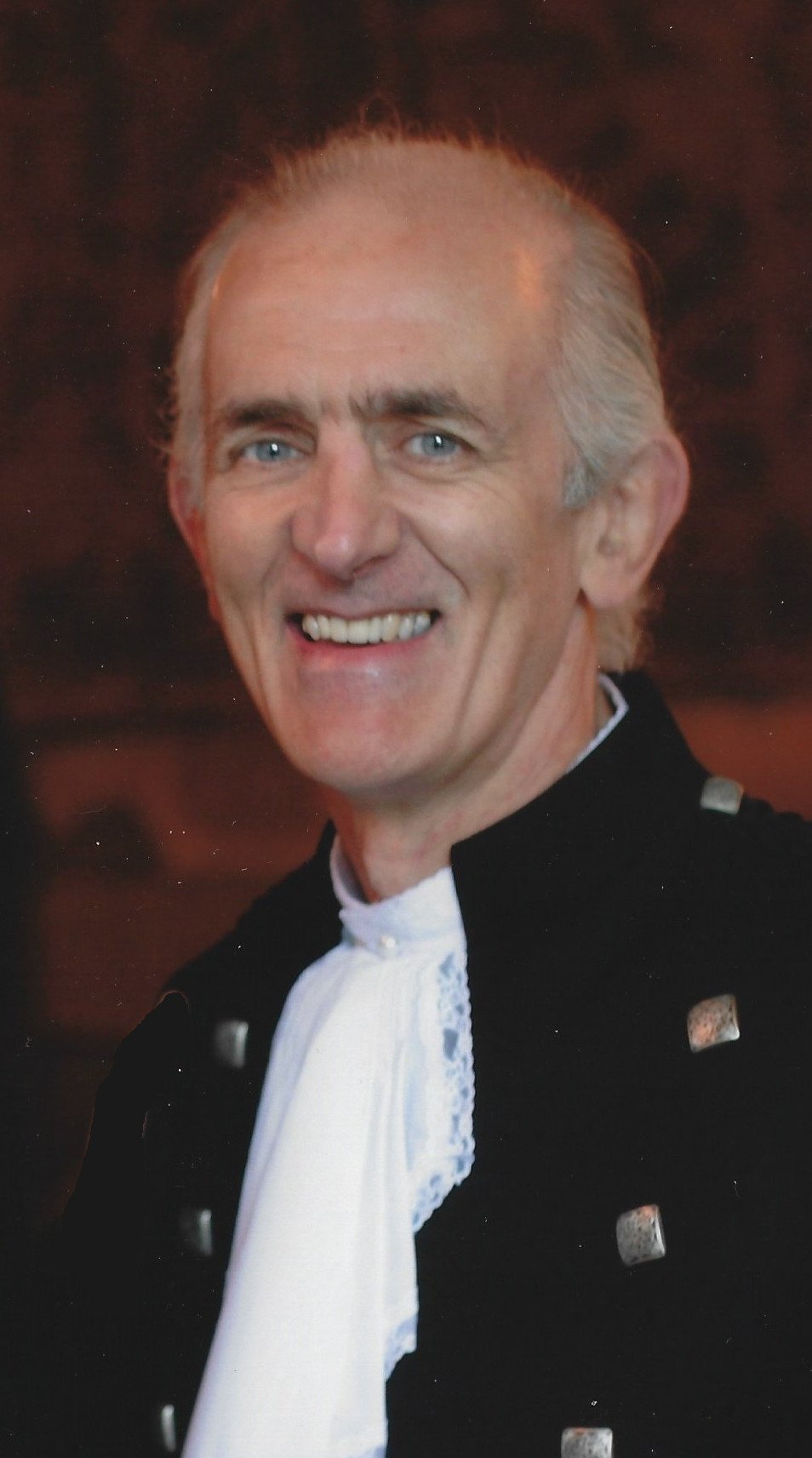

Archie Young died from Lewy Body Dementia on 17th March 2020, aged 73. Geriatric Medicine has lost one of its giants, and we have lost a friend, mentor and role model.

Archie’s passion was building the scientific evidence for the importance of physical activity to health and physical function in old age. Archie excelled in sport and physical activity; he was an international swimmer, an accomplished water polo and rugby player, fell runner, mountaineer, cyclist and an avid amateur triathlon and duathlon competitor. His mainstay was regular fitness training, hill walking and swimming, which underpinned his remarkable power and agility – even until the end.

Archie’s enduring legacy is in clinical practice and education, research and translating research into practice. He was born into a distinguished medical family; his grandfather Professor Archie Young, Regius Chair of Surgery at Glasgow University counted Albert Einstein, Marie Curie and Joseph Lister amongst his colleagues. His father, Dr Archie Young, was a highly respected anatomist also at Glasgow University.

Archie was awarded a first class BSc in Physiology from Glasgow University in 1969 and MBChB (commendation) in 1971. His appointments included Clinical Lecturer at the University of Oxford and honorary Consultant Physician in Rehabilitation Medicine (1981 to 1985), Senior Lecturer (1985 to 1988) and Professor (1988 to 1998) of Geriatric Medicine at the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine, University College London.

Professor Jerry Morris, the father of physical activity research, had the highest regard for Archie in their joint mission to link habitual physical activity to the maintenance of life-long health and independence. On appointment to the Royal Free Hospital in 1985, Archie integrated Health Services for Older People with General Medicine and with Old Age Psychiatry in his pioneering work with Dr Nori Graham. Archie was instrumental in establishing the concept of, and developing Queen Mary’s – a Rehabilitation Hospital for older people in Hampstead. While at the Royal Free, he set up a very popular undergraduate teaching programme in Geriatric Medicine, as well as extending his research interest in sarcopenia and frailty - long before the field became fashionable. At the University of Edinburgh, he led the development of the medical students’ Portfolio and Portfolio Viva.

Archie moved to Edinburgh in 1999 to take up the Chair of Geriatric Medicine. He set up a Human Performance Research Laboratory at the Royal Infirmary, as he had done at the Royal Free, to continue his work on the measurement of physical fitness and functional ability in older people. Additionally, he worked as an honorary consultant geriatrician for NHS Lothian. When he retired in 2007, his Festschrift, attended by people from all over the world, was a truly wonderful celebration. Especially memorable were the demonstrations of warmth, affection, and esteem, plus, of course, the evening ceilidh; Archie didn’t miss a dance!

Archie’s academic achievements were stellar. His research, beginning with investigations into skeletal muscle function and the reflex inhibition of arthrogenous muscle weakness, covered the effects of use, disuse, ageing and disease on skeletal muscle. In 1984/5, with Professor Maria Stokes, he reported how quadriceps strength and size correlated in younger and older women and men. He keenly investigated the concept of crossing ‘thresholds for independence’ and the influence of aerobic training (with Professor Carolyn Greig and Dr Katie Malbut) and resistance training (with Professor Dawn Skelton) on the restoration of independence in old age, i.e. ‘turning back the clock’ – particularly in the oldest old (see his visionary paper ‘Exercise physiology in geriatric practice’, Acta Med Scand 1986). With Professor Stephen Harridge he showed that an 85-year-old weightlifter was as powerful as a 65-year-old. He delivered these messages with great panache; during his inaugural professorial lecture at the University of Edinburgh, he squatted down, wearing his academic gown, and – to the audience’s surprise and delight- demonstrated the weightlifting techniques he had described in his academic paper.

Archie was passionate about translating research into practice and he strongly supported interdisciplinary working. In 2005, he and Dr Susie Dinan-Young, a leading specialist clinical exercise practitioner, co-authored a paper for the British Medical Journal entitled ‘Activity in later life’. They showed how habitual physical activity can help prevent disease and result in a wide range of health and social benefits in old age. They also provided specific guidelines on safe and effective exercise, and the professional training and qualifications needed to deliver, adapt and tailor exercise to the diverse individual health and functional needs of frailer older people.

Archie was awarded multiple honours and awards, including the Milroy Lecturer of the Royal College of Physicians of London, the British Council Visiting Professor (University of Zimbabwe), and in 1995, the inaugural Prince Philip Medal from the Institute of Sports Medicine. He delivered multiple international Principal Lectures, including the Marjory Warren Lecture. He was a member of the Research Advisory Council of Research into Ageing and the Scientific Committee of the British Geriatrics Committee. He received the British Geriatrics Society President’s medal in 2010.

Archie’s interest in physical activity extended beyond his work. His sporting achievements were also remarkable. At 21, Archie became the Scottish Amateur Breast Stroke Champion, when, in July 1968, he broke two Scottish records in 100 yards and 110 yards. He then reached the breaststroke final of the 1970 Commonwealth Games, and swam for GB in the World University Games. His record was broken only by the emergence of David Wilkie (who subsequently won Olympic gold in the Montreal 1976 Summer Olympics) so no shame in that!

He played competitive rugby for the Picts, the over 35’s team of the London Scottish Rugby Football Club. When Archie turned 50, he took up ice climbing instead; we remember with great pleasure discussing his weekend mountaineering exploits in the Scottish Highlands first thing on a Monday morning. On the second of Archie’s three treks to Everest, he took his daughter Sula (then 11 years old) and his son Archie junior, who celebrated his 10th birthday there.

Archie’s approach to the care of older people was meticulous; he always focused on what was best for the individual, and his practice was truly holistic. He was an inspiration to many geriatric medicine trainees who are now consultants and academic leaders. His PhD students, co-authors, and colleagues describe his enormous intellect, and how he generously shared his knowledge and expertise. He was a true gentleman who always had time for others, and who always treated members of his multidisciplinary team with the utmost respect.

He will be greatly missed by his family, friends, and colleagues. Our deepest condolences go to his wife Susie Dinan-Young, his sister Margaret, his children Sula and Archie with his first wife, Sandra Clark, and his four grandchildren.

This tribute was written by Professors Gillian Mead, Carolyn Greig, Frederike van Wijck and Dawn Skelton.