1. Introduction

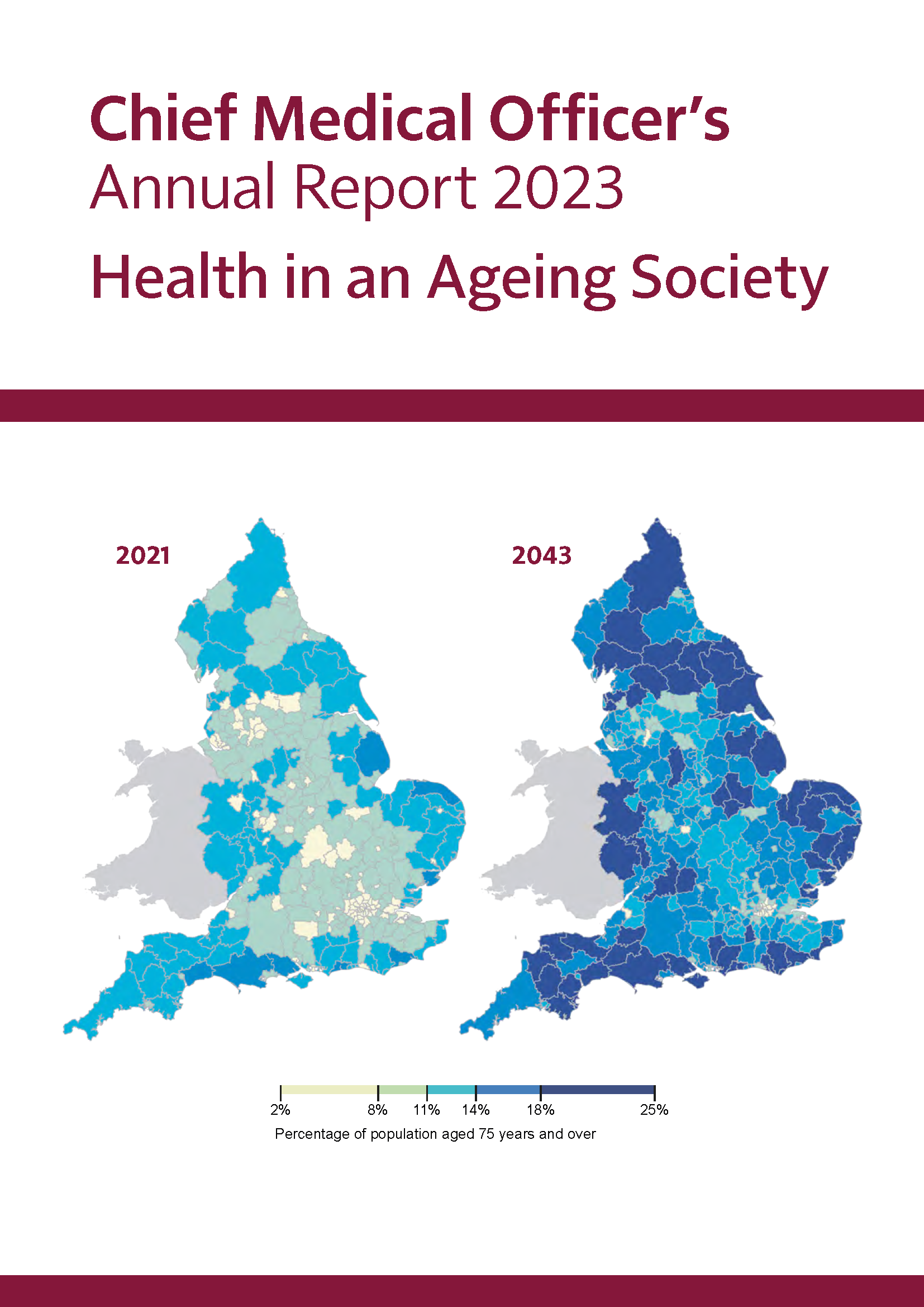

In June 2024, the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) hosted a roundtable event with senior leaders from across health, social care, charity, think tanks and the civil service to discuss the challenge set out in the Chief Medical Officer’s 2023 report about health in an ageing society. As the BGS, we have a unique role to play in bringing together a range of stakeholders to discuss issues related to healthcare for older people. After that first roundtable, we committed to convening the group again.

In October 2025 we brought together a similar group of leaders from across sectors to discuss older people’s healthcare. As before, our roundtable focused on the health system in England, though the issues discussed have wider relevance for the other countries of the UK. The purpose of our roundtable was to discuss how to overcome barriers to implementation of age-attuned care.

This report is intended to be a record of the event, sharing the discussions that were had and key advice for systems leaders aiming to ensure healthcare systems deliver the best care possible for older people now and for all of us as we age.