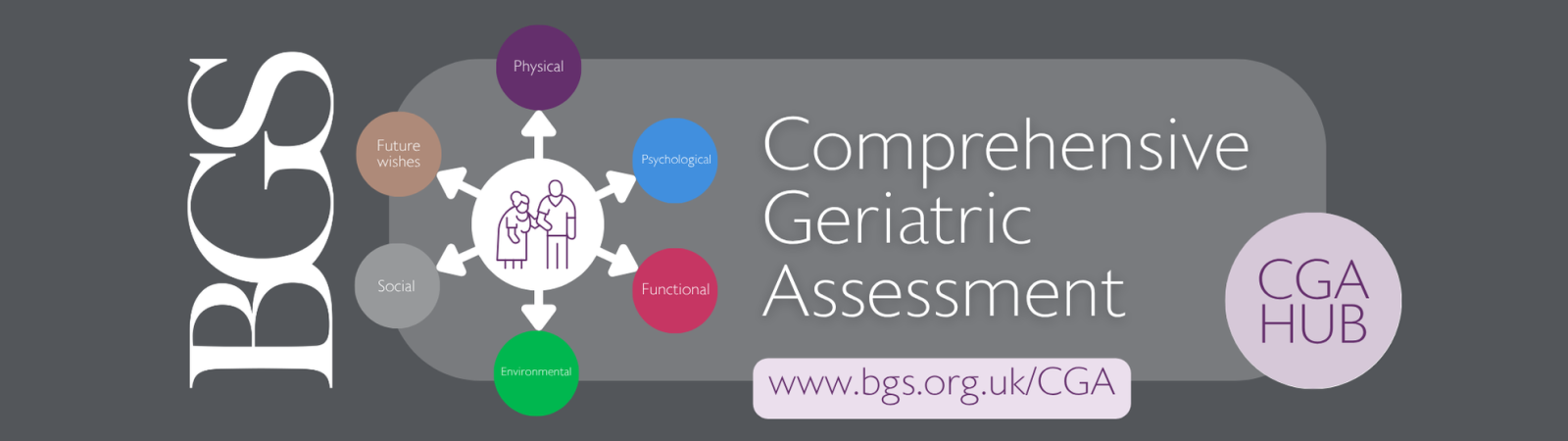

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) Hub

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a powerful, evidence-based approach to improving care for older people. By ensuring holistic assessment and coordinated intervention, CGA supports better outcomes across acute, primary, and community settings.

Navigating the CGA Hub

This page provides an overview of the concept and process of CGA and is divided into the sections below. Click the image to go straight to that section:

Image not displaying correctly? Click here to enlarge.

What is CGA?

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is the term used to describe a structured multidisciplinary approach offering gold standard care for older adults. It is evidence-based, and increasingly recognised for its role in improving quality of care of older people across various pathways and healthcare settings.

Rather than being viewed as an isolated assessment of need, CGA goes beyond a routine medical assessment and incorporates all physical, psychological, functional, social and environmental factors. These are then used to develop an integrated holistic care plan that is individualised.

When done well, we know that CGA leads to better outcomes for older people. It is important for all clinicians, health and care leaders and managers who have an interface with older people, to have an awareness and understanding of the clinical intervention and benefits of CGA.

Our CGA Hub aims to:

|

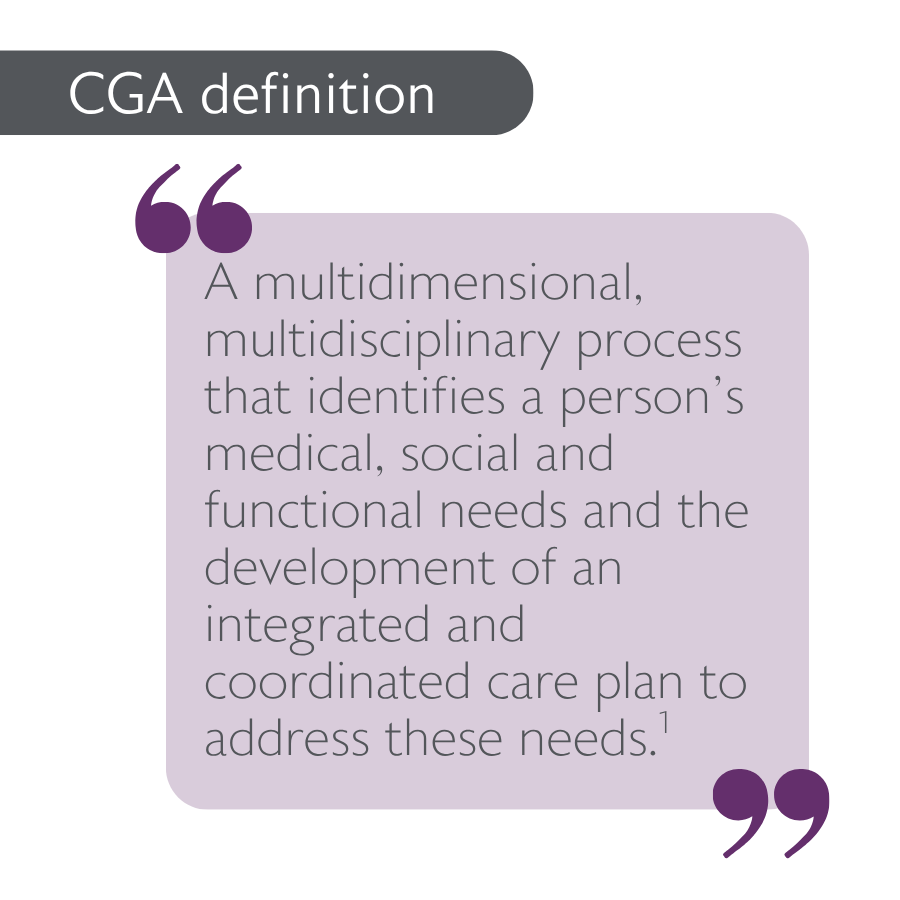

Definition of CGA

Despite its name, CGA is not just an assessment but a process of holistic care planning and coordination. It is defined as:

A multidimensional, multidisciplinary process that identifies a person’s medical, social and functional needs and the development of an integrated and coordinated care plan to address these needs." 1

The assessment format may be uniform, but the focus and problem list will be unique for each individual, leading to a personalised care plan that reflects their specific needs. It is also an iterative process rather than an isolated snapshot assessment of need, which is why a plan for follow up is included in its definition as older people with complex needs often move between different teams and pathways of care. In this regard, CGA can be used to co-ordinate care across boundaries and ensure care is less fragmented; providing positive effects for service users and services alike.

Why CGA matters: The evidence base

CGA has been shown to improve patient outcomes and optimise healthcare services across various settings:

- In primary care, CGA helps identify at-risk individuals living with frailty and/or multimorbidity and supports early interventions by co-ordinating care, reducing hospital admissions2. Medication optimisation in this setting may reduce the risk of death3 and functional decline.4

- In community settings, CGA has been linked to reduction in physical frailty5 and unplanned hospital admissions without affecting the risk of nursing home admission or death.6

- In acute hospital settings, CGA has its most robust evidence base, and has shown significant reductions in falls6, admissions to long term care facilities and delirium incidence.2

- In emergency departments utilisation of CGA by Acute Frailty Teams and Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC) has been found to result in lower admission rates, functional impairment and re-admission to emergency care.2

- In surgical settings, embedding CGA into perioperative pathways has led to better recovery, lower delirium incidence and reduced admission to long-term care facilities.2 Specifically, within orthogeriatrics, CGA has shown to improve mobility post hip fracture:6

CGA has demonstrated efficacy in various environments throughout various trials, with multiple benefits to both patients and clinical services. Embedding CGA into medical and surgical clinics for example has shown reductions in mortality, delirium incidence and prolonged length of stay in acute settings, in addition to increasing the appropriateness of medication prescribing.2

CGA should be recognised as a key component of any integrated care system’s approach to developing services for the population they serve. Building capacity for CGA is fundamental as outlined in the BGS Joining the Dots strategic document.7 If all older people living with frailty or multimorbidity received gold standard CGA across primary, community and acute care, this would lead to improved quality of care, better patient outcomes and a more sustainable NHS and Social Care system.

CGA domains

Click on a domain to go straight to that section.

Image not displaying correctly? Click here to enlarge.

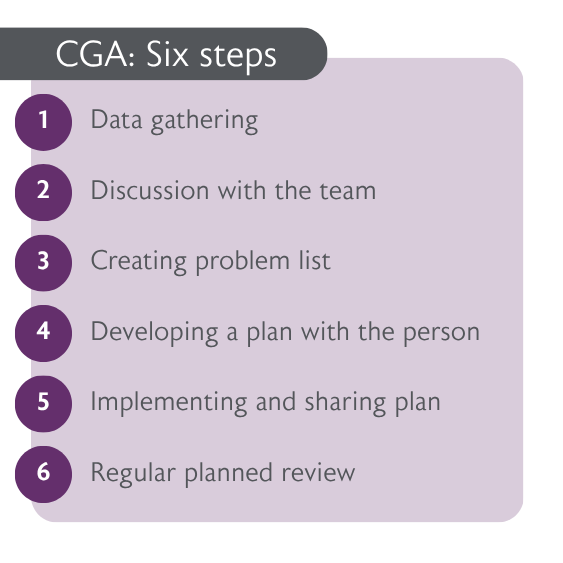

The CGA process

The process of CGA covers certain domains that must be included for holistic assessment and care planning. Each of these can be further divided into areas that will require different levels of focus, depending on the needs of the individual.

It is worth noting that there will often be significant overlap between these areas, which highlights the importance of a multidimensional approach.

CGA consists of six key domains, each essential for creating a comprehensive care plan:

|

1. PhysicalCovers medical history, frailty syndromes, long term condition management, multi-morbidity, polypharmacy and structured medication reviews, nutrtion, pain management, and falls risk. |

|

2. PsychologicalAssesses cognition, mood, delirium risk, mental health conditions, and emotional well-being. |

|

3. FunctionalFocuses on mobility, activities of daily living (ADLs/IADLs), gait stability, and rehabilitation potential. |

|

4. SocialExplores social support, carer needs, isolation, spiritual/reliious beliefs and financial concerns. |

|

5. EnvironmentalExamines home safety, accessibility, community services, technology aids. |

|

6. Future WishesIncludes advance care planning, treatment preferences, resuscitation status, and long-term care decisions. May include anticipatory care planning, which focusses on ceilings of treatment in an emergency should this occur in the future |

|

Next steps: ImplementationThis section offers some real-world examples and experiences of CGA being implemented into older people's services. We invite BGS members and colleagues to share their success stories, tips, and learnings. |

Throughout all these domains there should be a holistic approach, ensuring that the person is listened to and all interventions are tailored to what would allow them to live well with frailty and multiple long-term conditions in a way that aligns with their thoughts and values.

Consideration of care planning, goal setting and an exploration of any safeguarding issues should run throughout every domain. CGAs need to be clearly documented, available and visible to patients, in addition to their appropriate carers, relatives and health and social care workers. The ability to adhere to and ensure follow up can most successfully be achieved with everyone working from one editable CGA document.

Who performs CGA?

CGA is a multidisciplinary approach involving various professionals, each contributing unique expertise. While team composition varies, key members may include:

- Medical experts (Consultant Geriatricians, Associate Specialists; GPs with a Specialist Interest in older people and frailty; Consultant Practitioners; Advanced Clinical Practitioners): Often provide an overarching clinical lead role for the wider multidisciplinary team. Lead medical assessment and treatment planning.

- Nursing staff – Monitor health changes, skin integrity, nutrition and support holistic care.

- Allied Health Professionals (Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Speech and Language Therapists, Dietitians) – Address mobility, function, communication, environment and nutrition.

- Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians – Optimise medication prescribing and review polypharmacy risks.

- Social Workers, Social Prescribers & Care Coordinators – Address social determinants, care needs, safeguarding, and community support.

The coordination of this team of professionals should be led by clear procedures and pathways, and sustained by administrative support. In addition to the internal team, relationships with community partners, particularly within the Voluntary, Charity and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sector are vital for successful CGA.

When to use CGA

Frailty identification

CGA should be triggered for any older person who would benefit and is first reliant on identification of the need.

CGA is applicable in various settings and can be delivered in a proactive way; when the older person is not unwell, or in a reactive way, when the older person presents with urgent care needs. Although the elements of CGA remain the same, the environment in which it is carried out may alter the focus or goals for the individual. For example, conducting proactive CGA in primary care has been shown to decrease hospitalisation and re-hospitalisation.2 CGA remains beneficial as a more reactive process, with CGA in hospital medical and surgical wards demonstrating a reduction in delirium incidence and admission to long-term care facilities.2

Proactive CGA

Proactive CGA can be used for individuals identified at risk, or as living with frailty in the community setting, in primary care, or as part of work up for a surgical procedure.

Identifying those in need for CGA assessment can be through use of population health management tools that risk stratify cohorts of older people at a population level. The electronic frailty index is a tool that can be used to risk stratify patients on caseloads in Primary Care. It produces a score based on the outputs of 36 ‘deficits’ identified through approximately 2000 read codes.8 "This then requires clinical corroboration using a validated identification tool, such as the Clinical Frailty Scale.9 Any older person with a CFS score of 4 (vulnerable) or above is likely to benefit from a CGA approach. Within the community or primary care setting, early identification of frailty and those who would benefit from CGA should be a key priority.

Reactive CGA

Reactive CGA should be triggered when an older person enters crisis. This is often through recognition of one of the frailty syndromes, such as falls, impaired cognition or delirium, sudden changes in function and mobility, new incontinence or susceptibility to a new medication causing frailty crisis.

In the community setting, crisis may be assessed by a GP on a home visit, an urgent community response service, ambulance crews and Hospital at Home services. An urgent CGA approach is applicable in the acute hospital setting, including in organised frailty units, front door frailty teams working in the Emergency Department or acute medical units and Same Day Emergency Care. It is best delivered by specialist frailty multidisciplinary teams in these settings for older people with urgent care needs. See the Silver Book II for more information.

Explore CGA domains

The pages below will take you to a more detailed breakdown of each domain, and provide advice on how to embed CGA into your work.

References

Click to expand

- Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, et al. What is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age and Ageing 2018; 47: 149–155 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx166

- Pilotto A, Lora Aprile P, Veronese N et al. The Italian guideline on comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) for the older persons: a collaborative work of 25 Italian Scientific Societies and the National Institute of Health. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research (2024) 36:121 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02772-0.

- Bloomfield HE, Greer N, Linsky AM, et al. Deprescribing for communitydwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:3323-32.

- Ibrahim K, Cox NJ, Stevenson JM, Lim S, Fraser SDS, Roberts HC. A systematic review of the evidence for deprescribing interventions among older people living with frailty. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:258.

- Veronese N, Custodero C, Demurtas J, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in older people: an umbrella review of health outcomes. Age Ageing 2022;51:afac104.

- Kim DH and Rockwood K. Frailty in Older Adults. Published August 7, 2024.N Engl J Med 2024;391:538-548 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2301292.

- British Geriatric Society (BGS) Joining the dots: a blueprint for preventing and managing frailty in older people. Published March 2023. https://www.bgs.org.uk/joining-the-dots-a-blueprint-for-preventing-and-managing-frailty-in-older-people-0

- NHS England: Electronic Frailty Index https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/older-people/frailty/efi/#the-contract-requires-general-practice-to-use-an-appropriate-tool-for-example-the-electronic-frailty-index-efi-what-is-the-efi

- Rockwood Clincal Frailty Scale https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/attachment/2018-07-05/rockwood_cfs.pdf