Roman Romero-Ortuno is Associate Professor in Medical Gerontology at Trinity College Dublin and Consultant Physician at the Mercer’s Institute for Successful Ageing in St. James's Hospital, Dublin. Prof. Ortuno co-chairs the Frailty and Resilience working group of The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) and the Irish Frailty Network Interest Group of the Irish Gerontological Society. He is Faculty member of the Global Brain Health Institute. He tweets at @ProfOrtuno. Here he discusses their Age and Ageing paper ‘Is phenotypical prefrailty all the same? A longitudinal investigation of two prefrailty subtypes in The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA)’.

Over the past decade, many of us have become interested in the science of frailty. Even if we do not agree on how frailty should be measured in research or clinical practice, we all tend to agree that frailty means vulnerability to decompensation after stressors, as a consequence of cumulative decline in many physiological systems during a lifetime. We also tend to agree that the effect of chronological age in determining this risk is not as important as the underlying biological situation.

One of the many ways to measure (i.e. operationalise) frailty is the physical frailty phenotype. Briefly, this identifies someone as frail when three or more of the following are present: exhaustion, unintentional weight loss, weakness, slowness, and low physical activity. Prefrailty is defined as the presence of one or two criteria.

Many of us may have been phenotypically prefrail at various points in our lives. For example, those in a sedentary full-time job reporting low physical activity (with or without exhaustion), may already be prefrail. The same label applies to someone experiencing unexplained weight loss and slowness. Yet, are the underlying biology and future risk comparable across prefrailty scenarios?

To illustrate this point at population level we operationalised two mutually exclusive prefrailty groups in TILDA: one defined by exhaustion and/or unexplained weight loss (prefrailty “type 1”) and one defined by exhibiting one or two of weakness, slowness and low physical activity (“type 2”). Using data spanning an 8-year period, we found different longitudinal trajectories of mortality and disability, with prefrailty type 2 having significantly higher risk. This suggests that phenotypical prefrailty may be a heterogeneous biological syndrome.

Prefrailty has been proposed as a target for interventions aimed at delaying or reversing the disabling process. However, the population prevalence and incidence of prefrailty are very high. Given its biological heterogeneity, phenotypical prefrailty may be of low value for the identification of individual risk in real practice. In that light, professional societies such as the British Geriatrics Society do not recommend population screening for frailty using currently available instruments. Instead, best practice guidelines for the management of frailty focus on the identification of risk, helped by frailty tools, with a view to perform comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and implement tailored evidence-based interventions.

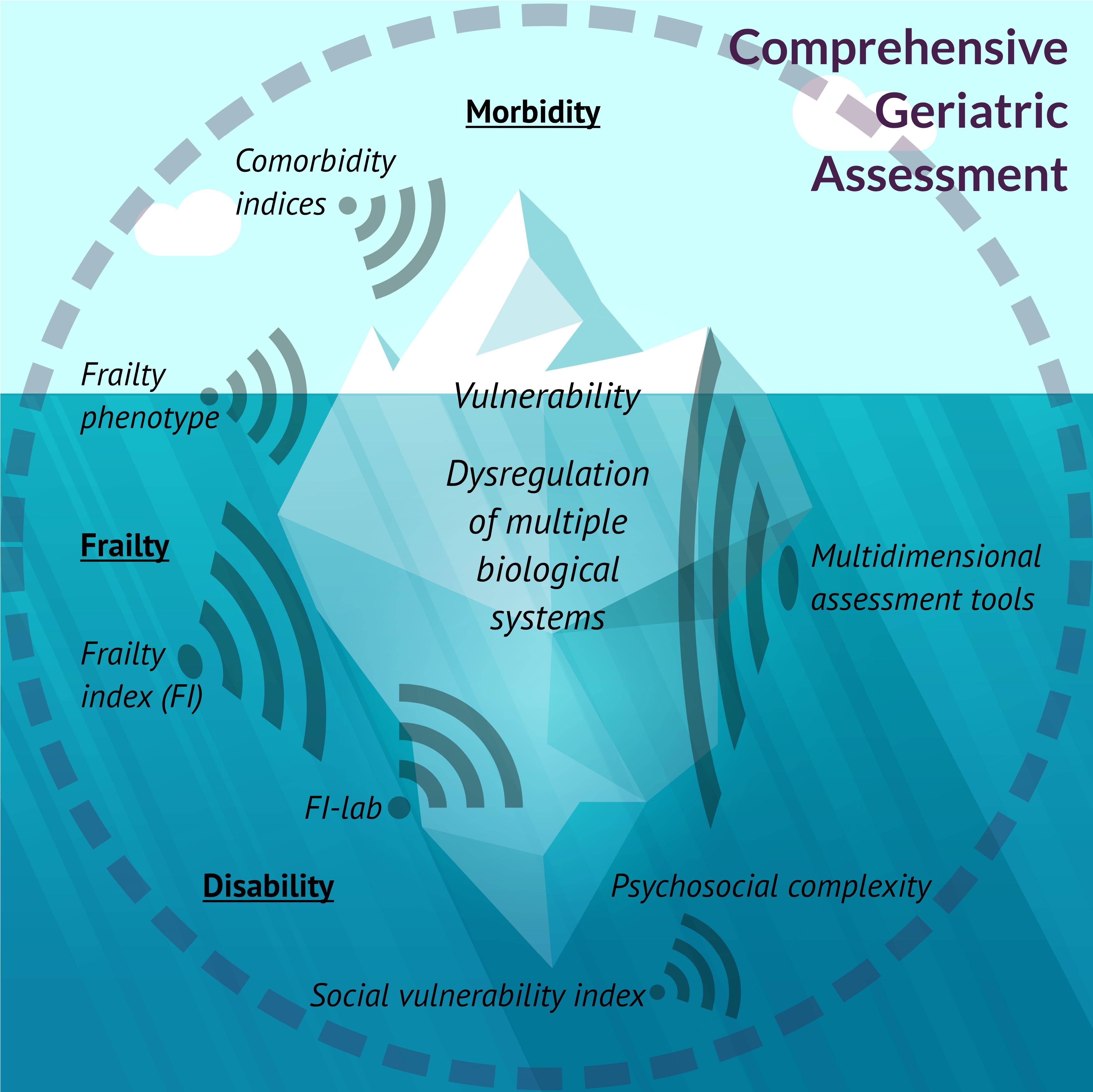

Frailty is a concept, not a diagnosis. Frailty can be thought of as an iceberg, most of which is latent and not visible to the naked eye (see figure). Yet, it can be indicated by different tools (like sonar beams of different widths) to help clinicians become risk aware. In turn, the drivers of that risk need to be unraveled and properly diagnosed using CGA, which will often identify remediable factors. As we discuss in our paper, even the identification of more homogeneous prefrailty subtypes does not provide a substitute for CGA, to diagnose the cause/s of frailty at an individual level.