Background

Wider context of this research

The term ‘frailty’ has many different meanings and applications. Age UK and the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) have identified how this varies amongst three key groups: geriatricians and other older people’s healthcare specialists, health care professionals without expertise in older people’s care and older people themselves.

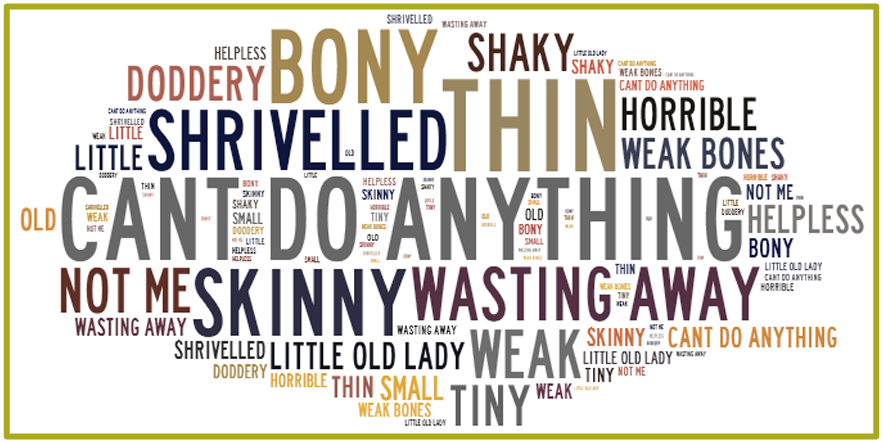

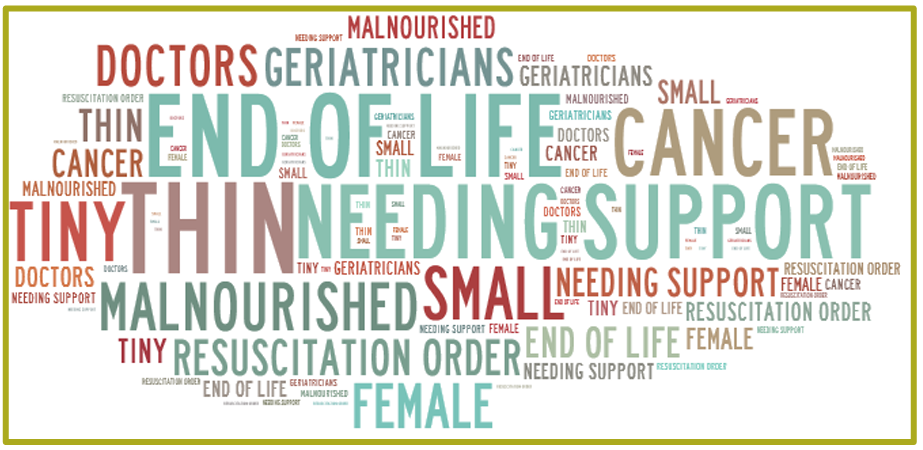

Among older people’s specialists the term ‘frailty’ is used to describe a spectrum of physical and mental health states and is used to assess risk or to put together a care plan for an individual. By contrast, non-specialist healthcare professionals (HCPs), with less experience of older people’s care are thought to be more likely to use the term as shorthand for older people with complex care needs or in late old age. Importantly, there is evidence to suggest that the term ‘frailty’ does not resonate with older people, nor is it something that they identify with. This has led some in the healthcare sector to raise concerns that, as a result, fewer older people may access the health and social care that they need. If true, this would have important implications to approaches to care for older people.

Purpose and objectives of this research

BritainThinks was commissioned by Age UK and the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) to undertake qualitative research to gain insights that can be used to help raise awareness of approaches to care that can prevent or minimise the impact of frailty on older people.

The target audiences identified as being key to this research were:

General public audiences, comprising:

- Older people, aged 69+, living with frailty

- Older people, aged 69+, not currently living with frailty

- Non professional, informal carers of older people living with frailty.

Professional audiences, comprising:

- Managers in hospital wards

- Practice and district nurses

- Non-specialist healthcare professionals, including GPs.

The research was designed to identify ways of supporting older people to:

- Identify with the concept of ‘frailty’ (if not the word)

- Engage with preventative strategies and frailty services (with support from healthcare professionals (HCPs) and informal carers)

- Play a role in accessing services (such as those providing the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment), that are designed to help them.

Ultimately, the research findings are intended to feed into strategies to help reduce the impact of frailty on older people’s lives. For a full list of project objectives, please refer to the Appendix.

Methodology and sample

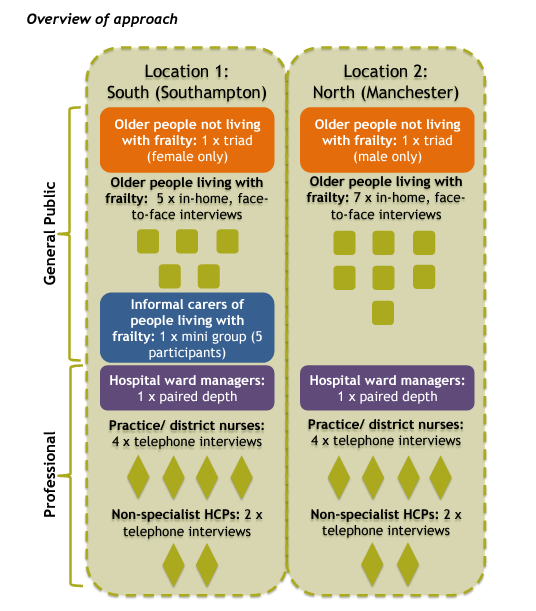

A research approach tailored to audience ensured that the specific characteristics and needs of each group were met. In addition, focussing on two fieldwork locations, Southampton and Manchester and surrounds, meant that findings were not affected by regional bias.

Research among public audiences:

- Interviews with older people living with frailty were conducted faceto-face and in-home to ensure that there were no accessibility issues for participants and that there was minimum disruption to their lives. It also helped ensure that participants felt comfortable sharing their views on a potentially sensitive and personal subject, as well as enabling the research findings to draw on observational insights as to how participants live in their homes. All in-home interviews lasted for 60 minutes.

- Older people not currently showing any outward signs of frailty, and informal carers of people living with frailty, were consulted in focus groups to enable comparison between different viewpoints and experiences.

- Those sessions with older people lasted 75 minutes and the group with informal carers lasted 90 minutes.

- The focus groups with older people were split by gender to try to ensure that the participants felt comfortable sharing their views and experiences. - All interviews and groups were qualitative and semi-structured, using a discussion guide developed in collaboration with Age UK and BGS to address each of the project objectives.

- Each discussion began with open questions before moving on to a more direct questioning approach, and the interviewer ensured that the spontaneous responses of each individual were gauged before prompting. The specific language that participants used and their non-verbal responses were also observed and used to inform later analysis. For a more detailed overview of the discussion content and stimulus materials, please see the Appendix.

Research among healthcare professionals:

- Hospital ward managers were consulted in paired depth interviews lasting 75 minutes, to reflect the time pressures facing this audience while retaining the opportunity for participants to share experiences and views.

- Interviews among practice and district nurses as well as nonspecialist HCPs were conducted by telephone, again to reflect the time pressures facing this audience. Each interview lasted for 40 minutes.

- Interviews were semi-structured, although there was more direct questioning than the approach taken with public audiences, since participants were not being asked sensitive questions requiring projective techniques.

- The discussion guide explored the healthcare professionals’ personal experience of the challenges associated with treating older people living with frailty, and their understanding of the concept of frailty.

Fieldwork dates

Fieldwork took place between 21st October and 5th November 2014.

Sample detail

The older people sample comprised:

- A spread of ages from 69+

- An even gender split

- A spread of socioeconomic grades

- A minimum of 3 BME participants

- A mix of older people who live alone and those living with others

- Among the audience living with frailty only, all participants showing outward signs of frailty and between 5-9 on the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale (see Appendix)

- Among the audience with no outward signs of frailty only, all participants between 1 and 4 on the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale.

Those in the carers sample all provide a varying amount of support for an older person living with frailty, and the group included:

- A good mix of ages

- A good mix of gender

- 1 BME participant

- A mix of carers who live with and live separately from the older person for whom they care

The professional sample was comprised of HCPs with:

- A spread of years of experience

- Inclusion of BME participants

- An even spread of practice and district nurses (among nurses)

- A range of areas of specialism (among HCPs who do not specialise in older people’s care)

Limitations to the research

The small sample sizes on this project and qualitative research method mean that the full scope of audience experience and opinion may not be represented in this report. No older people living in care homes or sheltered accommodation were consulted as part of this research, nor were any older people with a frailty score above 8, as measured on the Rockwood Frailty Scale.