It was the best job I have ever had, being a Consultant Physician on the Emergency Medical Ward (EMW) in Juba Teaching Hospital, South Sudan. It was 2011 and I was in charge of a vibrant and thriving ward, with two HDU beds, a reasonable abundance of life-saving equipment and drugs, and some highly trained staff. We were engaged in audits, research, teaching, and unlike any other ward, there was 24-hour consultant on call cover. Yet what I delighted in most was seeing the nurses and junior doctors grow in confidence as they gained experience and in witnessing their happiness when they knew that they had made a difference to a patient’s life.

This patient was critically ill with the “full house” of malaria complications- ARDS, rhabdomyolysis (see urine), AKI, anaemia, cerebral malaria, and hypoglycaemia. His death was a sad yet critical milestone in the evolution of our EMW. He did not die because he did not have access to basic life-saving equipment or medications. He did not die because of poor medical or nursing care (he had his own “HDU nurse”). He died when there was a power cut and the oxygen concentrator fell silent.

However, it didn’t start out like this.

When I first walked into the Emergency Medical Ward, I felt like I had gone back in time. The nurses were dressed in white uniforms with a matching white nursing cap, reminiscent of the NHS in the 1950’s. The ward was a traditional Nightingale design; there was a long room with a central corridor, punctuated by two rows of beds on each side. The paint on the beds was cracked and peeling with rust filling the gaps. The mattresses looked equally tired with a worn, stained centre from many years of overuse.

And on each of those beds, on mattresses laid out on the floor between the beds, amidst growing piles of rubbish and bodily fluids, were patients.

So many young, sick, patients.

So, in 38 degree stifling heat, with no skills in speaking Arabic, no medications or life-saving equipment, and a nurse to interpret, I commenced my first ever post take consultant ward round.

Many young people died that day. To the team, it was a normal day.

The journey to change was a beautiful tale of hardship, friendship, and working alongside some of the nation’s kindest and cleverest minds. However, I want to tell you a different story, the tale that unlocked all this change. This is a tale of my ‘awakening’; how I grew to understand our different cultural perspectives.

08:30 Monday August 25th, 2008. Three years earlier…

I was a young SHO who had completed 18 months of training. My educational supervisor, a South Sudanese consultant in the UK, had suggested that I and one of my friends (also a doctor) James, take a brief career break and spend four months working in Juba Teaching Hospital, South Sudan. A few weeks later, the plane touched down on the runway of Juba International Airport and we were escorted by our hosts to our lodgings, which in a hastily arranged twist of fate, also happened to be a Roman Catholic Commune owned by priests and nuns of the Comboni Missionaries of South Sudan. This twist of fate soon proved to be a stroke of luck; neither I nor James were particularly religious, but the Comboni’s did not seem to mind and many an evening would be spent in sublime conversation, listening to their lifelong experiences in South Sudan.

Our day would begin with a twenty minute walk to hospital. During the first days of our arrival- and about five minutes into our commute- I noted something familiar behind a fence that ran contiuous with the road. “James? Isn’t that building our office?”

“Um… yeah it is, I think.”

“It is, you know.” I looked ahead “And look there is a gate in the fence right next to our front door!”

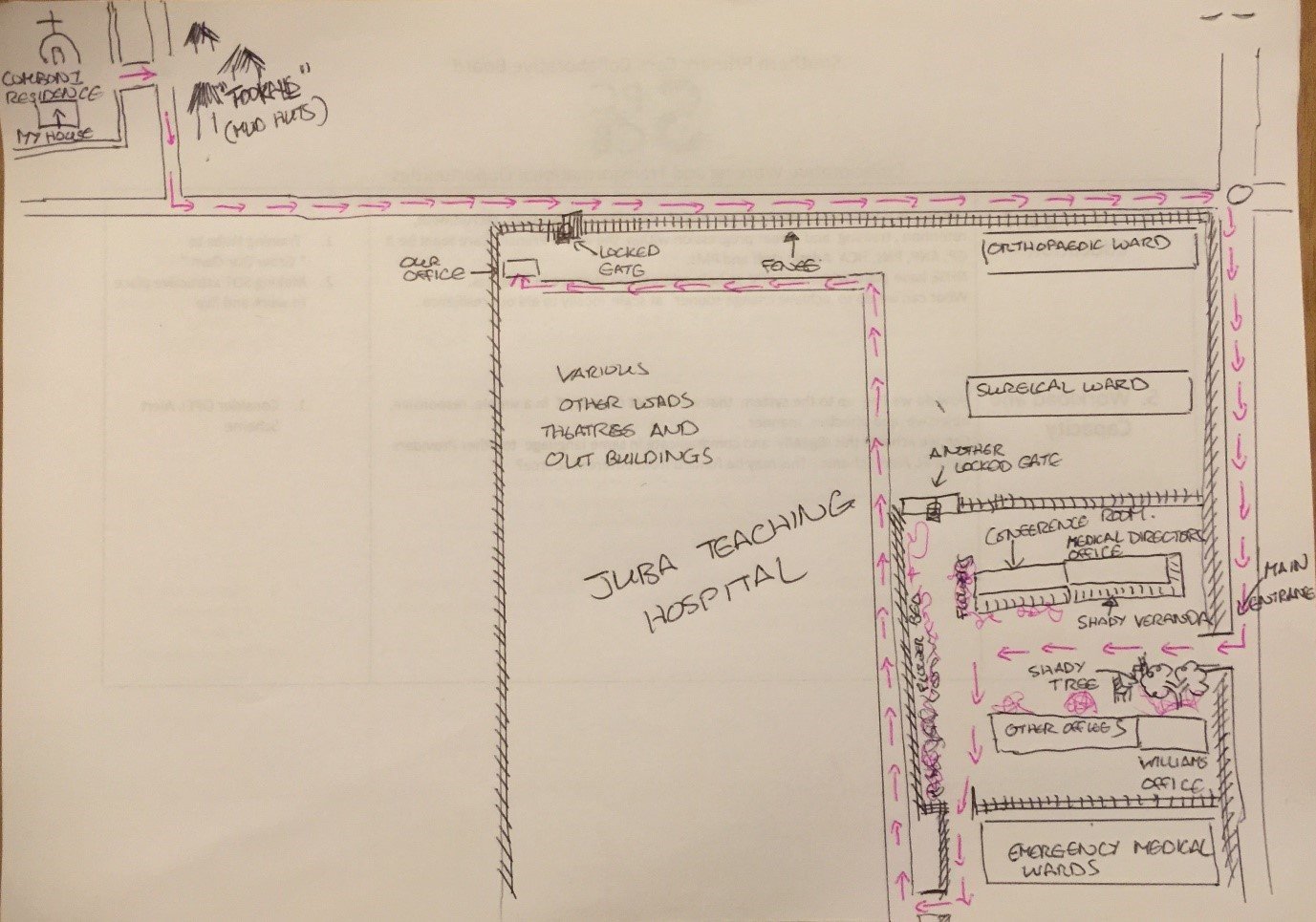

Any hopes of entering through said gate were dashed by a military grade padlock. We continued our usual journey and later that night James went on to Google Earth to see the journey we were actually doing, which looked annoyingly like the drawing below:

“What kind of utter, inefficient, pointless dysfunction is this? Absolutely typical for South Sudan!”

“Everyone is late.” agreed James “Even the rush hour is two hours late.”

For the next four months we resigned ourselves to walking past this gate in hot weather, staring longingly at our airconditioned office before continuing on for another fifteen minutes, negotiating our way through a medley of locked gates and tortuous routes that doubled back and ended up with us being in our office, having a beautiful view of our house a few minutes away.

13:10 September 25th 2008. A month Later:

“Can you pass me the soap, please?” I asked.

“What’s soap?” Asked sister Anna.

“You know, soap. The blue thing that we wash our hands with. The same blue thing we do our laundry with?”

“Ah you mean ‘sop’!” She laughed and passed over a well-used bar. “You khawaja’s speak such funny English.” Khawaja was a term used to refer to white people.

She then grabbed a small watering can and poured water over my hands so that I could rinse them.

“Now you are ready to eat with us, Dr David!”

The ward sisters were sitting around a coffee table, festooned with various South Sudanese culinary delights including greens (something akin to kale), eggplant with a delicious peanut butter source, goat, and the ubiquitous nile perch. There was no cutlery for this meal. You shared plates and ate with your hands.

“Would you like a drink, Dr David?” a carrier bag was produced with various cans.

“I’ll have a coke, please.”

“Coke?”

I had an inkling how this might be pronounced. “This one?” I pointed at the diet cola.

“Ah-ha you like ‘cock’.” She smiled, amused by the language difference. “Here you are.”

The food was lovely. “How do you think our first week of teaching went?” I asked. Anna and I had just finished a week-long course teaching the first cohort of nurses how to recognise and manage a sick patient and perform vital signs. The teaching was challenging - half the nurses spoke English and Arabic and half spoke only Arabic. Anna had very kindly agreed to be my interpreter. Prior to teaching I made her promise that if I was speaking too fast or not using the appropriate pronunciation, she would let me know.

“It was good.” She answered.

“Good?”

“Yes.” She answered flatly. Then shot me a smile “They said they understood you! Unlike the Irish nurse!”

I grinned. Prior to starting teaching, Anna told me about an Irish nurse who delivered exactly the same teaching at the School of Nursing. She told me how the nurses appeared attentive, nodding their heads to appropriate cues on the blackboard. The Irish lady had reported back to her Charity that the teaching was a spectacular success. The nurses reported back to Sister Anna that they couldn’t understand a word their teacher had said. Culture dictated that they keep quiet so as not to cause offense.

After that story I had made her promise to educate me about life and culture in South Sudan so that I could better understand things and not be “an ignorant Khawaja.”

“Dr David, you are eating with your left hand!” She said.

“Is that bad?” I asked.

Another kind smile, “that is the hand that we use when we are in the bathroom. The right hand is for eating!”

Oh dear.

That evening, I regaled James with the tale on the walk back.

“I don’t know how they put up with us, James. They must think that we are such a bunch of ignorant jokers!”

“I think they do like us, though.” James chimed in, “Otherwise they wouldn’t be helping with the teaching.”

“True…” My voice trailed off as I walked past the locked gate next to our office. “You know, I bet you there is a reason why this gate is locked. And I bet there is a really important reason why all the gates between here and our office are locked.”

“And I bet you,” James continued “That it will be the last reason we can fathom on this planet!”

16:30 December 13th 2008. Four months in...

It was our last day at Juba Teaching Hospital. We had trained 120 nurses in recognition and management of the sick patient. Sister Anna and I had taken some volunteers and given them advanced training in fluid-resuscitating septic patients. The EMW was locked and loaded with two cupboards full of drugs and life-saving kit. The drugs were only to be used for patients who were too poor to buy their own medications or if critically ill and a first dose was needed.

We then put the two together and stood back. The result was beautiful.

Septic, hypotensive, malaria-riddled patients had lines sunk into them on arrival, given boluses of fluids, and early anti-malarials. Some patients with severe malaria were hypoglycaemic. Many woke up on the end of a needle following a dextrose bolus. Those who didn’t were put into the recovery position and most improved by the next day.

Their care was reflected in a significant mortality reduction on the EMW.

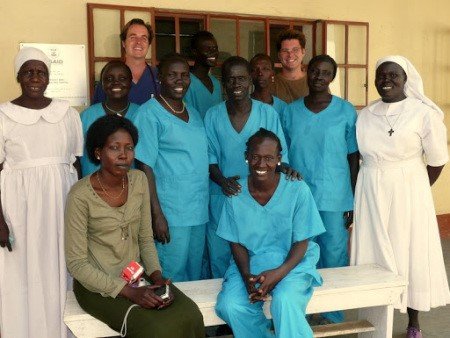

EMW nurses with Sister Anna sitting on the bench, left, on our last day at JTH. Sister Anna spoke to the Ministry of Health and all EMW nurses were given uniforms and promoted for their hard work - in a land where nurses barely earn enough to support their families, this was a massive morale boost.

The hospital Director, Dario, thanked us for our work. However, it was time to say good bye.

“We will miss you all.” I said “You have been warm and kind hosts and I have learned much about life, about myself, and about the people and the culture of South Sudan.”

James and I had immersed ourselves in South Sudanese life. We had experienced the full spectrum of human emotions from hardship to kinship, apathy to love, failure to success. We felt more ‘alive’ in South Sudan than at any point in our lives before or since.

A big handshake ensued. Followed by a hug.

The diesel engine of the Toyota Landcruiser hummed in the background. Our driver was ready to take us to the airport. I was about to leave when a thought dawned.

“Dario, one last question.”

“Yes?”

“For the last four months there has been one question that has always bothered us.” I narrated our commute to hospital for the last months. “Why are the gates, leading to our office always locked?”

He looked at us both and roared with laughter. “It’s the goats. They keep eating the flowers!”

The chair as weapon for change

If I were to pinpoint the single most effective weapon in effecting change in healthcare, it would have to be the chair. Change requires strong relationships, whether that be across cultures as in South Sudan, or across providers in the NHS. These are built on shared understanding of each person’s perspectives, respect, and trust.

There is no shortcut to this process, it takes time and conversation.

And the best place to have a conversation is sitting in a chair.

The conversation is the process. Understanding perspectives, respect, and trust is the output. Change in healthcare is the outcome at a macroscopic level. At an individual level the journey from ignorance to understanding imparts much wisdom and humility along the way.

A conversation in a chair - with my 2012 self

When I was a medical registrar in 2012, I would see my life through the lens of a hospital medic. I was respectful of GP’s but never really understood what they did - they just seemed to generate work and not seem to be able to do much with their patients. I looked at my hospital world and felt that every day, the entire community of older people with frailty and dementia would spill its guts and end up admitted under the medical take.

Patterns emerged; Older people with acute confusion hardly ever had a UTI, yet they were still being sent in as “confused ?UTI.” Everyone on a thiazide always had an electrolyte imbalance, yet still they were prescribed.

Worst of all were my vivid memories of seeing bedbound patients with advanced dementia, who had been yanked out of their care homes in the middle of the night to be admitted to hospital because they were peri-arrest. There, in A and E resus, I would see them and go through the motions. I remember thinking how unfair it was that nothing was happening in the community.

I wish I could have sat my “2012 me” in a chair and told them what I now do as a GP. I would have told them that my over-arching function was to manage 95 per cent of all urgent care encounters across the NHS, only admitting two to five per cent to hospital. To do that I would see 35-50 patients a day and process the bloods, medications, and letters on another 100-150. I would have told my “2012 me” that in primary care, it is uncommon for thiazides to cause electrolyte imbalance and a common cause of confusion and incontinence in an older people is in fact a UTI, although not the only cause! The vast majority are treated successfully and are never admitted, meaning that hospital doctors are naturally more likely to see other causes of confusion and incontinence in older people.

We would certainly have talked about end of life patients in care homes being admitted in the middle of the night. We would be in agreement that, with very few caveats, it would not be in their best interests. However, I would suggest to my “2012 me” that many of these patients are kept out of hospital and the hospital teams never get wind of them. This is due the close working relations that GP’s have with other teams such as palliative care, district nursing, care homes and a medley of other services that are essential in a person’s care. I suspect the colour on my “2012 me’s” face would have drained when I told him the sort of things that are kept out of hospital!

In my next conversation in a chair, I might have told my “2012 me” some of the limitations we face as GP’s. Ten minute slots enable us to fulfil our role; to keep 95 per cent of patients out of hospital. This comes at a price.

We have limited ability to monitor a patient to check for improvement or deterioration. As a result, high risk patients need admitting for monitoring. This working pattern also means that every ten minutes, we have to make a complex decision about diagnosis and treatment that can have massive ramifications on 50 people and their families every day. It is really hard and takes a lot of listening, concentration, and skill. It leaves one feeling very tired.

GP surgeries are all privately owned companies that are contracted by the NHS to perform a function. Some might say this is a disadvantage; it makes us more “money orientated” as doctors. However, we are businesses and need to generate an income to pay our staff, just like bigger hospital organisations. Many strategic initiatives percolate their way through primary care and generally speaking, if you speak to a GP about “good medicine” you will get little disagreement. If you ask a GP to do this as extra “good medicine” in addition to their current work, you may sometimes see our feisty side! All GP’s would like to do more proactive care; I would love to spend my time doing advanced care plans and de-prescribing on older people in care homes. However, doing this will have a massive impact on our urgent care capability and the magic 95 per cent number. The best we can do is be a bit opportunistic, until funding arrives for extra staff to develop a new service.

There is one great thing about being a small private business; we are dynamic and incredibly nimble. Issues are brought to partners meetings and decisions are made and acted upon immediately. No other NHS organisation is this rapid to adopt change. This is an incredibly useful tool for driving innovation in response to urgent care demand and as a result we have evolved to be as lean and efficient as possible. The ace in our deck is certainly primary care IT; it records our data, dispenses our medications, links with hospital and community IT systems, processes bloods, Xrays, and letters, manages our rotas, does all our audits and coding, manages our workflow, and allows us to design customised, pre-populated letters and proformas for every conceivable situation known to medicine. I challenge hospital clinicians to find an IT system that can fulfil all these roles.

And I put it to hospital clinicians that if they had our IT systems, urgent care demand in hospital would be more efficient, too.

So ends my introduction to our GP tribe and our tribal perspective. I hope it helps you understand us better. However, the conclusion to this story deservedly lies with one last poignant thought from Sister Anna.

Whilst in the EMW in 2011 I joked with her about something she had forgotten and said, “Sister Anna, you have the memory of a goldfish.”

“What is a goldfish?”

“It is a fish that we put in a tank.”

“Do you eat the fish?” She asked.

“No.” I scratched my head and thought about how best to answer this one. “We just, kind of, watch it swimming around, I guess.”

“You Khawaja’s!” She laughed gently. Then she joked “And you people think that we South Sudanese are stupid?!”

I imagine Sister Anna might have chuckled at the irony of seeing my “2018 me” and my “2012 me” sitting in a chair in our cross-cultural dialogue. However, she would have approved.

Because she taught me that all of our tribes are special. And if we want to make this world a better place, the secret lies in sitting in a chair and understanding.

The next article will explore how the concepts of tribalism and tribal perspectives may be built upon to create the structures needed for change in healthcare. It will, of course, feature more tales from South Sudan, including a wise Dutch professor in Public Health who offered up a simple, yet devastatingly effective formula for transforming care.

David Attwood

GP