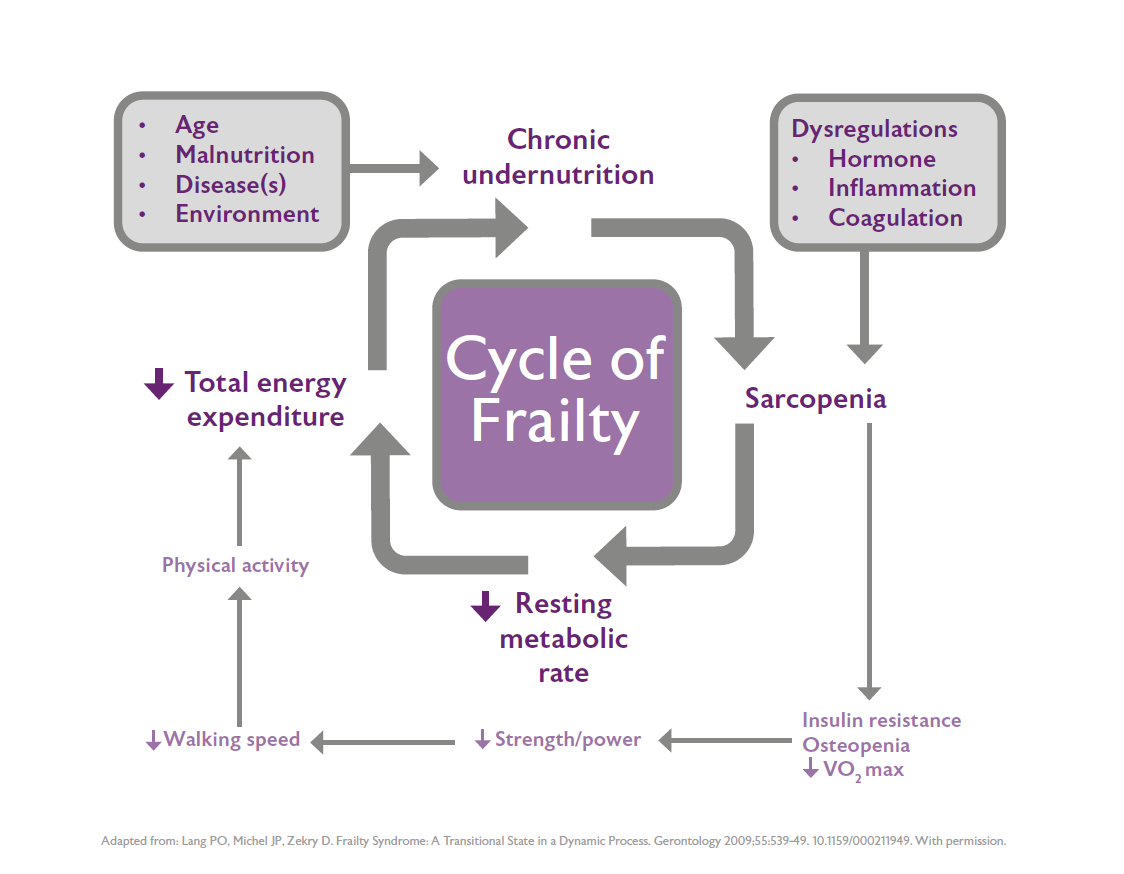

Frailty and malnutrition are linked; Fried’s frailty phenotype includes unexplained weight loss as one of the cardinal features of frailty.1

Malnutrition in older people is under-recognised in the UK because many people, including older people themselves, perceive low body weight and unplanned weight loss (malnutrition) to be a normal part of the ageing process. When identifying and managing frailty its good practice to screen for malnutrition and take action based on local NHS guidance which has been produced by or written in partnership with NHS dietitians.

People living with moderate or severe frailty may be categorised as being in the last year of life, however they may not be imminently dying and therefore from a nutrition perspective should be treated in the same way as any other patient. This means that their nutritional status should continue to be monitored using a validated screening tool (e.g. MUST or the Patients Association Nutrition Checklist) and efforts should continue to be made to work with them and their carers to meet their nutritional needs if possible. Meeting nutritional needs can help to:

- Maximise muscle strength.

- Maximise quality of life.

- Ensure other palliative treatments are as effective as possible.

Social interaction and enjoyment

Nutrient requirements can be met by tube feeding/parenteral nutrition/hydration, however this does not necessarily result in improved prognosis, for example in end-stage dementia. Moreover, other needs including enjoyment of food, the social aspects of eating together and simple human attention and interaction are not met by these routes of nutrition/hydration and should not be neglected.2 Providing food in a form that is palatable to the patient (such as finger foods), offering snacks and frequent small meals rather than large meals, fortifying food (such as adding skimmed milk powder or ground almonds to porridge and soups), and paying attention to the social aspects of eating (such as sitting around a table and eating together) are all strategies which can improve nutritional intake and enjoyment of food.

Food means much more to most people than simply nutrition, and at the end of life enjoyment of even small amounts of food and fluid is more important than its nutritional value.

Alleviating relatives' anxiety

Once the person becomes very severely frail at the very end of life (last few weeks or days) it is normal for the person’s interest in eating and drinking to decline. This can often be more distressing for relatives than for the person themselves, and reduced food intake (and the weight loss associated with it) can be perceived by relatives as the cause of death, rather than as part of the dying process.3 Families may also perceive that healthcare staff underestimate the anxiety and distress that reduced food intake and weight loss causes to patients and families.4 Management of reduced oral intake therefore requires in-depth discussion with the patient, family and staff involved, which should be an ongoing dialogue rather than a once-only conversation.5 One study found that relatives found reassurance in receiving written information on food and fluids at the end of life6 (click here for an example of such a resource).

Many families find it helpful to look at other ways in which they can provide ‘nourishment’, comfort and support for their loved one, such as providing mouthcare,5 but in some cases the family feel strongly that alternative forms of nutrition and hydration should be provided to the very end of life. If the patient retains capacity then their decision should be respected. However if the dying person does not have capacity (which is often the case), then the person’s Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) for health and welfare should be consulted, or if no LPA has been appointed, a best interests decision (balancing the benefits and burdens of the intervention and taking into account the views of family) should be made. In this situation it is important to remember the overall goal of care is to promote a good death, and continuing intravenous or subcutaneous hydration or tube feeding may or may not be the best way of ensuring this outcome.

References

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-56.

- Druml C, et al. ESPEN guideline on ethical aspects of artificial nutrition and hydration. Clinical Nutrition 2016;35(3):545-56.

- Friedrich. End-of-life nutrition: is tube feeding the solution? Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2013;2110:30-33.

- del Río MI, et al. Hydration and nutrition at the end of life: a systematic review of emotional impact, perceptions, and decision making among patients, family, and health care staff. Psycho-Oncology 2011;21(9):913-21.

- Clark J, et al. Declining oral intake towards the end of life: how to talk about it? A qualitative study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2017;23(2):74-82.

- Raijmakers NJ, et al. Bereaved relatives’ perspectives of the patient’s oral intake towards the end of life: a qualitative study. Palliative Medicine 2013;27(7):665-72.

Resources