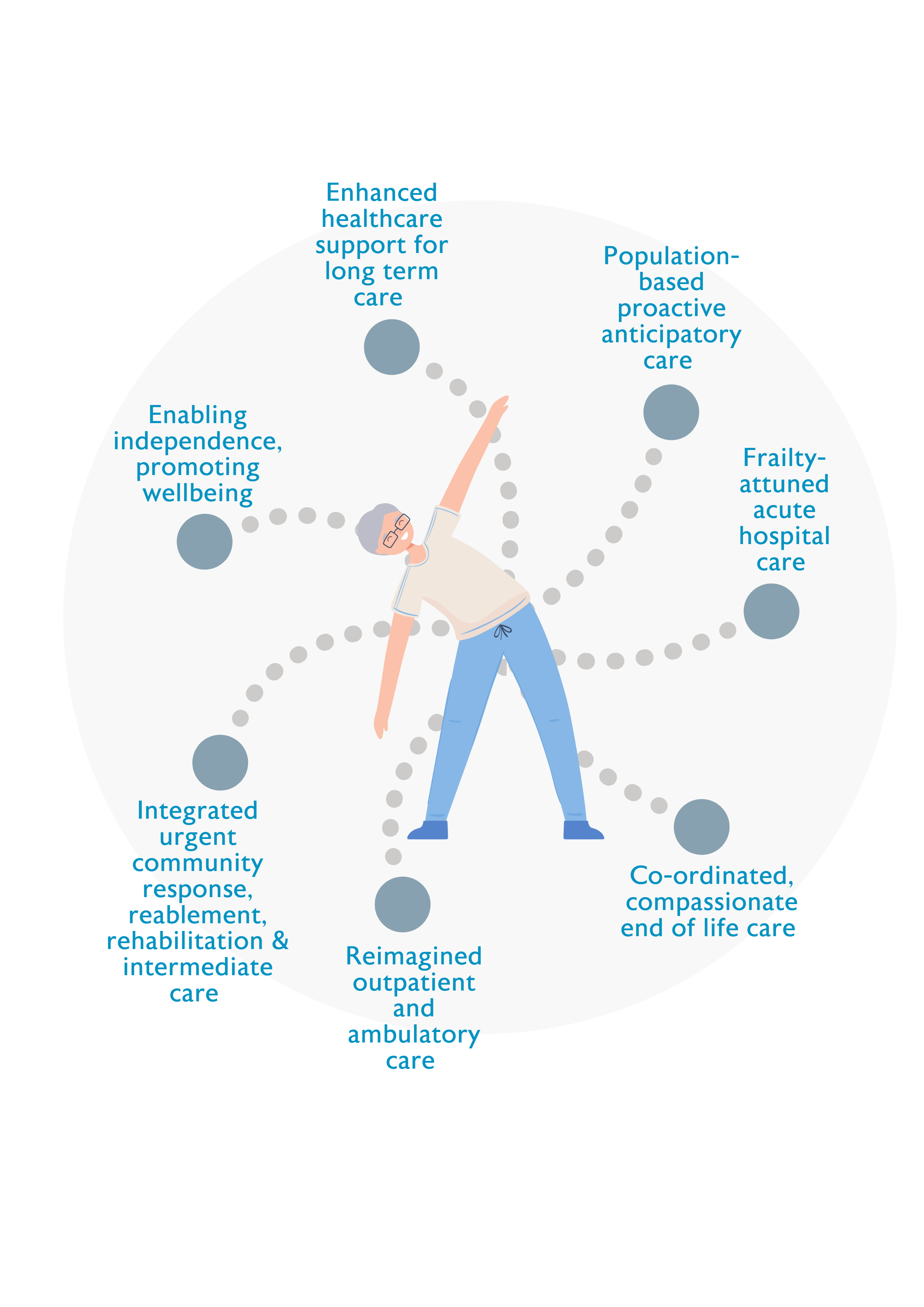

The evidence-based approaches and interventions that are required to prevent and manage frailty across the continuum of care are interdependent and mutually reinforcing and should be designed as ‘wrap around’ services that are available for all older people, wherever and whenever they are needed. Services that are designed around the needs of older people will reduce the number of people admitted to hospital as an emergency, promote early discharge home, and ensure that fewer people are readmitted to hospital or to long term care. This in turn improves outcomes for older people and reduces costs for the NHS and social care.

Enabling independence, promoting wellbeing

Case study

Make Movement Your Mission (MMYM), developed by the Later Life Training charity, broadcasts freely accessible 15 minute ‘movement snacks’ three times per day on Facebook (live and recorded) and YouTube. The key message, ‘sit less, move more’ applies to all ages and abilities. Participants (age 40 to 90+ at home and in care settings) include people with neurological or musculoskeletal conditions that need regular movement to slow progression or reduce symptoms. Participation and activity levels are promoted by support from the online instructor, Facebook messages pre and post live sessions, peer support, and self-motivation from noting improvements in balance and posture. Feedback indicates that the regular short movement snacks are felt to be achievable, provide a routine and offer opportunities to engage with others. In an independent evaluation, 90% of respondents said they moved more frequently and regularly every day; 53% reported better quality of life; and up to half reported improvements in activities of daily living (ADLs). Participants on waiting lists for joint replacement were kept mobile and had less pain.

Other examples

Mid & East Antrim Agewell Partnership (MEAAP), Ballymena, Larne & Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland

www.meaap.co.uk/impactagewell

Age Friendly Manchester

www.manchester.gov.uk/info/200091/life_over_50/8388/find_out_about_age_…

Other useful resources

- BGS Healthier for Longer (2019)

www.bgs.org.uk/healthierforlonger - World Guidelines on Falls Prevention and Management (2022)

https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article/51/9/afac205/6730755