Executive summaryHealth and social care services across the UK are under immense pressure. Images of ambulances queuing outside emergency departments (EDs) and horror stories of older people lying on the floor for hours waiting for an ambulance after a fall or waiting for hours on trolleys in ED have become commonplace across the media. Evidence shows that older people wait longer than other age groups to be assessed in the ED and to be seen by a medical specialist. Older people who are admitted to hospital are more likely to face lengthy hospital stays and are often unable to be discharged because of a lack of social care or rehabilitation in the community. Identification of frailty at the hospital front door can help trigger early comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and ensure that older people with frailty are diverted to the most appropriate services within the hospital as quickly as possible and, where possible, discharged home on the same day. As well as improving the experience and health outcomes of older people attending hospital, front door frailty services improve patient flow and reduce pressure on the whole hospital system. There is no ‘right way’ to do front door frailty – the service provided will depend on factors such as the hospital estate, the workforce available and the needs of the local population. With this in mind, we have set out to provide five principles that should underpin front door frailty services and support colleagues who wish to establish these services in their own localities: 1. Prioritise the development of the service In order to embed a front door frailty service, there needs to be an appetite for change across the hospital. A focus on improved patient flow and early discharge can help to foster willingness to change the approach to managing care for older people at the front door. Focusing on these benefits will help to demonstrate the potential impact of front door frailty to hospital managers and to make the case for change. The development of front door frailty services requires a quality improvement mindset. A small pilot project can help to prove that the service is needed within the hospital and that it can make a difference to patient experience and flow. Constant measurement of how the service is functioning is crucial to ensuring an ongoing cycle of improvement. 3. Map your organisation and consider intervention points Hospital design and workforce vary across the country and it is not possible to provide a definitive map of what a service should look like. It is important however that those wishing to implement front door frailty services understand what their hospital and the surrounding services look like and where front door frailty would fit within existing services. This includes liaising with community services, ambulance services and other specialties within the hospital. 4. Identify frailty and trigger the start of CGA By prioritising the early identification of people with frailty in the ED, CGA can be triggered as quickly as possible, ensuring that older people with frailty receive rapid treatment by the most appropriate team. Most new front door frailty services use the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) as an admission criterion to a new service as the CFS is easy to use and can help to ensure that the service is deliverable in the early days. However, as the service matures and referring teams better understand which patients are appropriate for front door frailty services, staff may find that admission criteria can be less rigid. 5. Build relationships and plan the workforce Those developing front door frailty services must invest time in developing relationships with colleagues across the hospital and beyond, including in emergency and acute medicine, hospital managers, community services and social work. Building trust between services is essential to ensuring the service becomes embedded in the hospital. The service must also be multidisciplinary, making particular use of colleagues in advanced clinical practice roles and encouraging involvement from across the team. These five key principles alongside a series of practical tips are intended to support colleagues establishing front door frailty services and help systems to ensure that older people presenting to the hospital front door are fast-tracked to the most appropriate services. This improves patient experience and outcomes and helps to improve patient flow across the hospital. |

Introduction

Front door frailty services (FDF) exist to identify people living with frailty as soon as they present to a hospital, to ensure that they are diverted to appropriate services as quickly as possible and, ideally, to ensure they are discharged to their normal place of residence (home or care home) the same day. Evidence suggests that these services benefit older patients as well as reducing pressure on hospitals. They have had a positive impact everywhere they have been introduced.

There is no ‘right way’ to do front door frailty – models vary depending on the staff available, the geography of the local area, the needs of the population and the hospital estate. In this document, we aim to summarise what these services might look like and provide practical tips to colleagues looking to establish front door frailty services. This document has been developed by a BGS clinical fellow through research and discussion with colleagues working in established and new services. It is intended to support healthcare professionals in setting up new front door frailty services and making a business case to managers.

This document is not a ‘how to’ guide for front door frailty services. Rather it uses the experiences of others to set out some principles to guide those wanting to improve the experiences of older people at the front door of the hospital. This document comprises three sections. The first section sets out why front door frailty services should be prioritised and why we need to focus on people living with frailty. The second section suggests five principles to guide people looking to set up front door frailty services with advice from colleagues around the country who work in established services. The third section includes take-home tips intended to help and inspire those wishing to establish these services in their localities.

Who is this resource aimed at?

It is widely accepted that there is significant variation in FDF practice related to hospital design, local geography, population demographics, and healthcare provision. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on service development and redeployment of staff affected FDF service delivery at many sites. Mirroring an established service may therefore be inappropriate due to these variations. Services need to be customised to each locality and this toolkit will focus on the principles of establishing a front door frailty service. It is aimed at clinicians whose FDF services are in their infancy, those struggling to develop new services or those whose FDF services have stagnated in their development and who are looking for further ideas and inspiration.

1. Why do we need front door frailty services?

Our population is ageing and this brings with it the challenge of increasing numbers of people living with frailty and multimorbidity. This population have ever more complex healthcare needs and, accordingly, the demand on our healthcare services is rising.1 Frailty is a distinctive health state related to ageing in which the body loses its inbuilt reserves, affecting an individual’s ability to recover from periods of ill health.2 Frailty affects up to half of people aged 85 and over,3 half of all hospital inpatients and care home residents and costs UK healthcare systems £5.8billion per year.4

Currently more than 60% of hospital beds at any one time are occupied by patients aged over 65 years and these admissions are associated with an increased rate of mortality,5 length of stay, high rates of readmission and institutionalisation. The unsustainable nature of the traditional models of inpatient focussed care for those with multimorbidity and complexity has been recognised at multiple levels, as evidenced by its prominence in recent healthcare policy documents from the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) and the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) as well as at government level. Prompt recognition and proactive management of frailty6 is becoming a priority for the NHS. The Silver Book II7 shares this view. New approaches are clearly required to allow for the provision of timely and effective care for older people living with frailty.

‘Front door’ refers to the part of a hospital where patients initially present when they are unwell. This may be an emergency department or an urgent care centre with patients arriving either by ambulance or independently. Front door frailty services deliver Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) to older people or people with frailty which can reduce pressure on hospitals through supporting same day discharges and help these people leave hospital sooner. Prompt CGA has a number needed to treat of 33 for one older person with frailty being alive in their own home in 12 months.8 If the opportunity for quick discharge is missed, then patients are at risk of long hospital stays which are associated with poor outcomes. Early supported discharge removes the risk of getting stuck in hospital and the associated harm. There is evidence that FDF services are effective in achieving quick discharge for older people living with frailty.8 NHS England has set out priorities for acute frailty calling for all localities to offer an urgent community response (UCR) service9 as well as utilising virtual wards and hospital at home services to avoid hospital admission, support early discharge and ensure optimised recovery through rehabilitation.

Effective FDF approaches screen older people for frailty, assess them and proactively manage their care so that they are supported to return home, ideally the same day, without having to be admitted. Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) and BGS have recently published their six-step guide10 for better care of older people in hospital which focuses on effective care to reduce hospital-acquired dependency and hospital admissions through increased use of community services. The winter months typically see increased presentations to hospitals with services struggling to provide high-quality care. This results in older people waiting too long for ambulances, waiting on trolleys in Emergency Departments (EDs)11 and getting stuck in hospital waiting to be discharged. This is not the care that older people want to receive and is not the care that healthcare professionals want to provide. Innovations to reduce hospital admission and reduce length of stay for those who require admission are urgently required.

2. Principles for setting up a service

We have identified five principles that those wishing to establish FDF services should follow. This section details these principles and shares tips from sites that have established services.

Principle one: Prioritise the development of the service

To establish an appetite for change in our complex healthcare system, space and time are needed to allow for this to develop. Focusing on patient flow and early discharge can help to embed this change. Without this focus, patients are more likely to have long hospital stays and, consequently, poor outcomes. Prompt decisions and interventions can reduce the risk of patients getting stuck in hospital, and if you get it right first time you can reduce the bed base downstream. Focusing on flow can demonstrate the impact that senior healthcare professionals with expertise in frailty can make at the front door and create a common narrative with management to support this change. Hospital management teams need to understand the clinical impact that a FDF service can offer, and the interventions that are needed to fulfil the wider aims of the organisation whilst also serving the needs of the individual patients. Involving an Improvement Manager can enable project oversight, expertise and maintain the momentum of improvement.

Development of a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) enhances the transparency of the service that is being provided and reduces variation in its delivery. To mitigate concerns over a change of service model, small, measured tests of change, with appropriate permissions and governance, can help to predict the impact of the change.

Top tips from the development journeys of experienced sites:

- Start somewhere, start small. Don’t be disheartened if it doesn’t seem possible to get a service fully operational from the outset.

- Establish a clear vision:

- e.g. every patient to leave in a better condition, and to add value with every interaction.

- Include timelines and goals to maintain sustainability of funding streams.

- Establish what is the demand or gap in the current system:

- e.g. time to complete CGA, bed moves or length of stay.

- Complement services already in place, avoid duplication of work.

- Get all key stakeholders involved for a collaborative approach, including the executive team to ensure all are aware of current policy drivers and understand the expectations from management.

- Support the change and evolution of the service with enthusiastic and dynamic staff, from its conception and throughout the development.

- Use funding opportunities or availability of physical space as a lever for change.

- Be curious. Embrace ongoing learning from long stay patients or community service relationships to further develop patient selection for frailty service input and timely discharge.

Principle two: Prove your need

Developing a service requires a quality improvement mindset. Creating a small pilot project will enable colleagues to prove to management that there is a need for the front door frailty service and that the implementation of such a service can deliver results for patient outcomes and patient flow. This pilot project will allow a test of concept alongside building trust in the new service. This will then require a test of change to care delivery and further redesigns in cycles of improvement. Tools such as process mapping and driver diagrams help to understand the functioning of each healthcare system. These tools also help to make the vision clear and improvement process transparent. Statistical Process Control charts are a useful method to compare impact of interventions across the improvement cycles. The Acute Frailty Network can provide bespoke service improvement support.

Measurement of how the service is functioning is crucial to its ongoing delivery. As there is such variation between existing frailty services and how they operate, it has been difficult to collect comparable data. All the experienced sites consulted for the development of this resource were interested in the development of a national dataset to enable them to compare outcomes and learn from others. This would encourage a culture of data collection and measurement of FDF services, helping to identify indicators of effective front door frailty care. This unified dataset could be used to inform the research happening in these areas and identify further FDF service development areas, for example the potential use of telemedicine in SDEC expansion. Data sharing agreements would be required to make this feasible. NHS Benchmarking plan to develop a data network as a structured benchmarking tool alongside the data analysed by GIRFT, Scottish Care of Older People (SCoOP) project, SAMBA audit and other relevant data.† FDF services can span emergency medicine and acute medicine audit criteria so it will be important to ensure that data collection is not duplicated.

Top tips on proving your need:

- Get all stakeholders around the table, establish collaboration with community services and commissioners, and hold ongoing improvement meetings throughout service development.

- Involve patients in the service design.

- Raise the profile to board level.

- Use data and patient stories to illustrate the impact of the service through a collaborative improvement method of Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles.

- Allow time to establish relationships and embrace a dynamic uniting improvement culture.

- Listen to the whole MDT and provide space for all to have a voice, gain trust and build relationships to ensure the project remains connected to those working in the clinical setting.

† SCoOP: www.bgs.org.uk/SCoOP

SAMBA audit: www.acutemedicine.org.uk/samba

Principle three: Map your organisation and consider intervention points

As there is significant variation in population, hospital design and workforce across the country, there are a range of approaches and models being used for FDF. Ideally a front door service should remain geographically close to admission areas to ensure good communication and complement processes already in place. A collaborative design method is needed to establish a service that is suitable for the local demand. In this section we outline some of the key components of FDF services, regardless of model used.

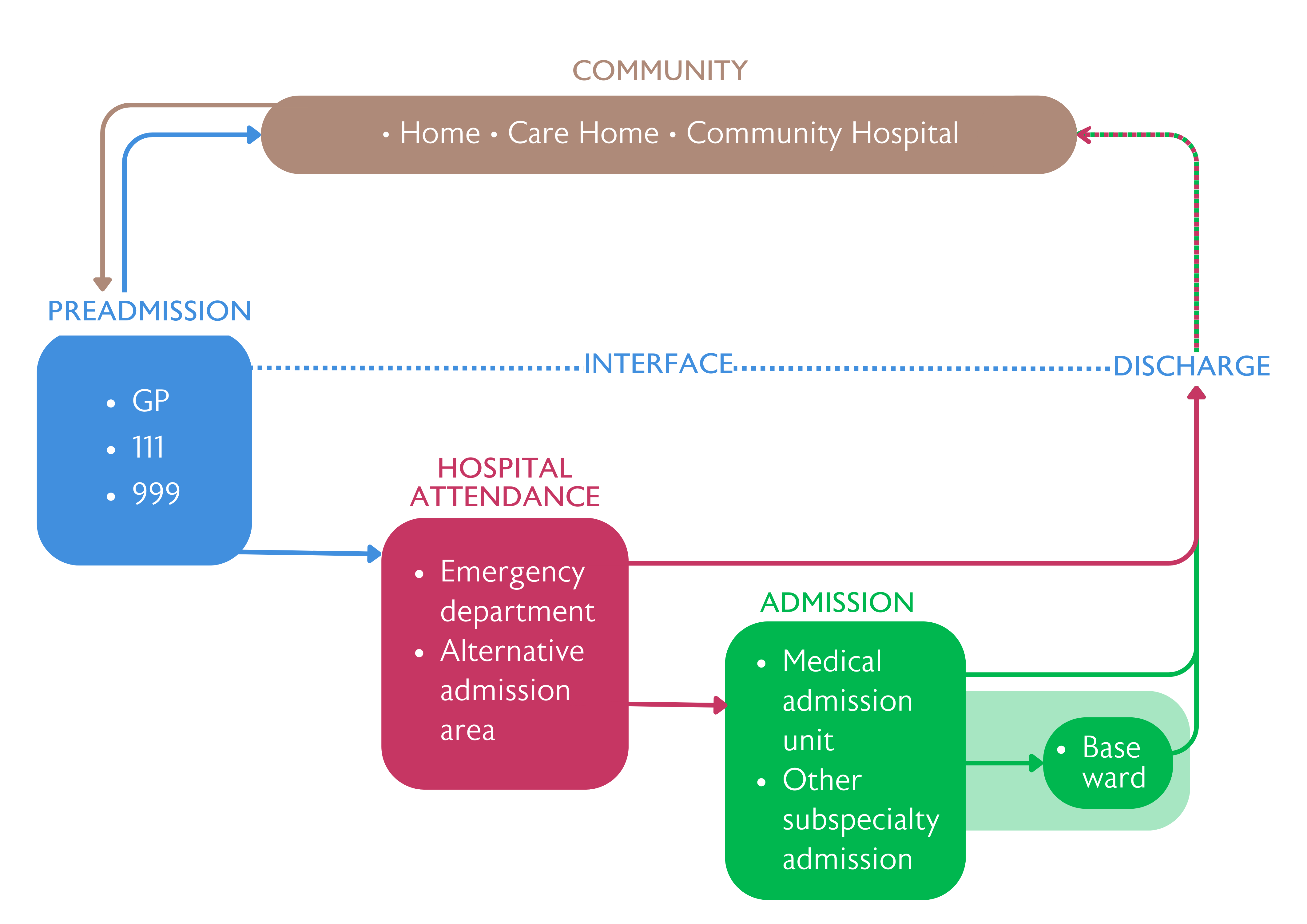

Preadmission

Silver phone or Consultant Connect: Connecting community services with specialist frailty secondary care advice facilitates an expert assessment of the patient’s needs. This optimises their care by community-based interventions or scheduled secondary care review using services such as Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC). As patients with frailty are often conveyed to hospital by ambulance, this is a sensible point of intervention and would aim to avoid hospital attendance where possible. This system is run by a frailty team usually managed by a geriatrician working on a frailty or SDEC unit or as part of a service providing frailty expertise to EDs (known as frailty in reach).

Example: An ambulance team were sent to an older patient who has fallen in their home. The paramedics are able to establish no injuries requiring immediate hospital conveyance but recognise the immediate falls risk. Paramedics are then able to refer to a frailty team who schedule falls follow up review, avoiding unnecessary admission.

Front door hospital attendance

Frailty services working within the ED can facilitate proactive rather than reactive patient reviews and prioritise getting the right patient to the right team as quickly as possible. Frailty services should focus on identifying those with complex needs that the ED does not have the capacity to address. Unwell patients with frailty often require more comprehensive and joined-up management. Prioritising patients who have recently been discharged from geriatric medicine wards or patients attending from care homes can be effective as these patients can often be managed by the FDF service and it is more likely that admission can be avoided and prearranged social care can be maintained.

There has been concern over the impact of FDF services on the four-hour wait limit in EDs. Trust needs to be built up using data that demonstrates that services can have a positive impact on admission avoidance and ED workflow. Collaborative design of services is needed to ensure that services operate successfully. We have outlined below two of the common designs for FDF services:

In-reach or liaison work

This is the method most used for initial scoping work of front door frailty services, for example a limited service to prove concept. Rapid reviews taking place at ambulance arrival can enable early commencement of CGA to limit the risk of deconditioning from the point of arrival to hospital and provide an increased opportunity to discharge without an increase in care needs. Many sites have promoted the role of Advanced Clinical Practitioner (ACP) alongside therapy teams to support the ED with identification of patients who are able to be managed in the community with simple interventions. They can initiate a CGA independently with close support from a geriatrician and enact referral to community services. These teams have also been able to develop specific pathways for common conditions affecting older patients with frailty such as fracture, loss of independent mobility or falls with head injury. This can enable rapid structured assessment for potential community management. In-reach teams can also review patients who have been deemed appropriate for admission and are awaiting a bed to identify those who could instead be diverted to frailty units or SDEC. In-reach teams can also work as mobility assessment teams for more straightforward reviews, to complement the work in the frailty unit.

Some advocate this approach and feel it reduces potential inequalities in patient care as teams can go to the patient without reliance on hospital flow. A roving service may enable more patients to be seen, delivering SDEC as a process not a place. However, concern has been raised over focussing all resources on the front door. Covering large areas of the ED and admissions can spread the team and dilute MDT efficiency.

Frailty ED space

Creation of a dedicated space to review patients with frailty within the ED can enable the MDT to work more effectively. It can provide two-way learning opportunities and upskill the teams to pick up on subtle presentations through repeated direct collaborative working. Patient selection can be through ED admission screening for case identification. However, some have found that moving to a designated space can interrupt investigations initiated by the ED and remaining within ED can facilitate rapid onward referrals.

SDEC or frailty unit

As with the frailty ED space, a frailty or SDEC unit can provide the designated area for rapid MDT working and can develop from proof-of-concept projects. Many Frailty Units function with dual purpose: to provide an assessment SDEC area as well as a bedded frailty area for those who are likely to require admission and need a proactive approach. This co-location enables sharing of the MDT resource and the ability to take a bigger spectrum of patients with frailty. These units are designed as a more suitable location for assessment of patients with frailty, for example providing space to wander and a calmer environment to that of ED, alongside staff who have the skill set to manage patients who may have cognitive impairments. The SDEC space can also be used as a ‘hot-clinic’ for scheduled reviews through an admission avoidance pathway, although ensuring this maintains rapid access is

a priority.

Intentionally reducing the number of trolley spaces can encourage mobility and reduce deconditioning. Scoping projects are needed to understand the levels of patient capacity needed to enable the unit to work effectively, and to gain an appreciation of estimated frailty SDEC admission rates. An initial high admission criterion (e.g. Clinical Frailty Scale [CFS] score 6 or greater) may be needed to ensure a deliverable service, balanced by a caution that this may limit its impact. Units must ensure that patients maintain equity of access to emergency inventions and specialty opinions, regardless of where they are cared for. Expansion of increased service hours should aim to match the demand of frailty presentations and potential same day interventions achieved.

The availability of a senior decision-maker close to the front door can enable frailty teams to review more complex and unwell patients. There is clear evidence of the benefit a timely review can have on patient outcomes.4 Senior decision-makers are also necessary to provide oversight of the ED and SDEC caseload and therefore maintaining patient flow. Continuity of senior decision-makers is also beneficial as it enables proactive management. Some established sites have noted variability in service delivery due to consultants’ different approaches to tolerating risk within the acute geriatrics setting. A clear standard operating procedure (SOP) or review template is essential to ensure a unified approach to risk.

Patient-centred practices have encouraged some sites to have a rolling take rather than formal post-take ward rounds at a specified time. Having touch-point meetings (huddles) throughout the day encourages proactive working. Timing of these meetings is important to ensure actionable interventions on the same day. Follow-up work through phone calls or community interface interventions such as virtual wards can help to facilitate early supported discharge.

Some established services have raised concerns about the risk of lack of flow and exit block when creating a designated frailty unit space. For an SDEC unit to function effectively, proactive flow management and ring-fencing of beds is required during development of the service.

Community and interface teams

Knowledge of the available community services and the funding and management streams that dictate them is essential to enabling FDF services to connect with community care. Creating an open dialogue and involvement in service development furthers integration of services. Geriatrician engagement with interface services facilitates further community linkage and supports two-way learning across the MDT. There is added complexity when the hospital catchment is supported by multiple community providers, so services can vary depending on locality.

The lack of social care in the community remains a problem across the country, contributing to avoidable hospital admissions and delayed discharge. In the short term, supporting families to assist with care needs may help to reduce these admissions and support early discharge. This however relies on patients having families who are willing and able to provide care, and it risks exacerbating inequalities.

Early supported discharge can be assisted through:

- Virtual Ward or Hospital at Home teams.

- Discharge to assess pathways.

- General practitioners with specialist interest (GPwSI), who can support the proactive workstreams of community frailty interventions, alongside care home reviews and proactive patient discussions.

- Local Age UK branches and other voluntary service providers such as the Royal Voluntary Service, who can provide support, e.g. welfare calls.

- Community Specialist Nurses e.g. Heart Failure or Respiratory Specialist Nurses.

- British Red Cross, who offer discharge support e.g. getting the home ready.

- Hospice at Home provision, with pathways in place to ensure seamless patient referral when needed.

- Community Geriatricians, to develop connection of services.

- Silver phone or Consultant Connect services.

- Rapid access CGA clinic.

- Community hospitals.

Other pathways

There are other hospital-wide pathways that focus on supporting our patients with frailty including perioperative pathways, delirium discharge pathways and reducing deconditioning pathways. Those working in FDF services should be aware of these pathways in their locality and build relationships to ensure ease of access for appropriate patients.

Principle four: Identify frailty and trigger the start of CGA

Prioritising the identification of frailty in the ED triggers review of people with frailty by healthcare professionals with the skills to manage frailty syndromes. Most sites are using the CFS embedded on the electronic ED system alongside a prompt in the medical clerking. CFS scoring is a quick, reproducible method that requires minimal training and is feasible to implement.6 Many feel that the frailty score prompts ED staff to think about frailty within their management and can play a role in getting patients to the right place as quickly as possible.

Using the CFS as an admission criterion to a new service is likely necessary to make sure that it is deliverable. Ideally, as the service matures the referring teams will understand which patients are suitable for the front door frailty team and the referral criteria can be less rigid, or non-existent, to enable capture of the patients requiring a CGA who may sit outside these parameters. From the recent BGS Frailty and Urgent care SIG survey, 75% of responders identify frailty in ED, with 50% and 28% also identifying frailty on Acute Medical Units (AMUs) and SDEC units respectively. Problems have been identified with embedding the assessment and robust use of the screening tool as it is often a non-mandated parameter within IT systems.

Parameters frequently used for frailty service input are:

- CFS score.

- Age.

- NEWS score.

- Admission from a care home or receiving care at home

- Admission with a frailty syndrome, dementia or Parkinson’s disease.

Patients are excluded from the service if they are presenting with acute stroke, for polytrauma assessment, fracture requiring surgery or require high dependency or intensive care unit admission.

Concern has been raised about CFS being implemented but not having any impact on how the service is run and taking time to embed. Variable completion and quality of CFS scores are common but on-the-spot education of staff to maintain the level of frailty interpretation has proved effective. A focus on the dialogue between referring teams and frailty services allows the healthcare professional to learn what a FDF service can offer.

Principle five: Build relationships and plan the workforce

Relationship-building

A priority of developing a FDF service is building relationships between departments and services currently managing people with frailty. These can include emergency medicine, acute medicine, hospital managers, community services and social work. Working together encourages learning from each other and creates opportunities to upskill colleagues in frailty identification and care. Experienced sites recall difficulty starting the process within the ED and acute medicine, and report that this difficulty was overcome by building relationships and gaining trust, thus enabling the service to progress.

Frailty team workforce

CGA requires MDT working to be delivered effectively and the required workforce staffing can demand change from traditional models of secondary care provision. The challenge now is how to support and empower the MDT to deliver this care. Touch points or co-location of staff encourages effective MDT working. Staffing gaps need to be identified early with proactive recruitment, alongside MDT roles being defined to ensure the right people are performing CGA.

Top tips for workforce planning:

- Advanced Clinical Practitioner (ACP) and Consultant Practitioners:

- Develop a culture of supporting nurses and therapists to progress into ACPs or Consultant Practitioners.

- ACPs typically develop from nursing or therapy roles working closely with senior decision makers. These progression routes to ACP and Consultant Pracitioner grades create a method to retain and increase the impact of experienced clinical nurse and therapy resource rather than experienced staff moving into managerial positions.

- Investing in these roles and encouraging individuals to develop in this way has resulted in many sites seeing a lower turnover of staff. It is important to ensure appropriate pay banding for their skill level and contribution to the service.

- ACPs can provide consistency to service delivery and help to educate rotational junior doctors.

- ACPs often coordinate and run FDF services and are skilled at managing protocol and medicine delivery.

- Some individuals considering an ACP role may appreciate the opportunity for a secondment before taking a post.

-

Senior decision maker, e.g. Geriatrician:

-

This enables rapid input to patients with increased complexity.

-

Enthusiastic clinicians, with an interest in acute frailty, are required to move to the front door to make these services work. Back fill for the roles left vacant is essential to ensure patient flow is not impacted.

-

The on-call requirements need to be considered e.g. General Internal Medical (GIM) take – working out which patient cohort will have already been seen to avoid duplication and create a successful job plan.

-

A lack of available geriatricians can hamper service development. Established services encourage use of the wider MDT but highlight the need to maintain geriatrician input in FDF work.

-

- Other senior decision makers e.g. ED/acute medicine clinicians/General Practitioner with Special Interest (GPwSI):

- Build on the workforce delivering the service.

- Further the development of relationships between services.

- Therapists:

- Encourage role blurring of therapists, to enable a specific dedicated frailty MDT at a FDF generic functional assessment. This allows for more robust services as it can be provided by all therapists involved.

- Front door social worker liaison role:

- This role provides a connection to community services, care homes and the community hospital bed base to facilitate priority discharge and can help to keep care packages and placements open when patients are admitted for a short time.

- A discharge co-ordinator role also enables liaison with relatives to alleviate concerns about early discharge and can offer a safety net though a follow up phone call.

- Further subspeciality liaison:

- Mental health and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) management.

- Palliative care and hospice at home identification.

- Specialist Frailty pharmacist

- Emerging roles for speech and language therapists (SALT) and dieticians at the front door.

3. Take-home tips

|

Definitions and acronyms

Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS): Developed by Professor Kenneth Rockwood at Dalhousie University, Canada. An inclusive scale of function and dependence variables that is validated in people over 65 years of age.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA): ‘a multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process to determine the medical, psychological and functional capabilities of an older person with frailty in order to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up’. In practice the collaboration of a range of professionals including specialist nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and social workers led by a geriatrician or general practitioner with a specialist interest.12

Driver Diagram: A tool that can be used to help plan improvement project activities. It is essentially a classic ‘tree diagram’ commonly used in operational research.13

Frailty: A health state related to ageing, of increased vulnerability associated with decline in reserve and function across multiple physiological systems.2,14

Front door frailty services (FDF): Services that operate in a multi-disciplinary fashion at the front door of hospitals. Working within or near the emergency departments or patients’ point of access, with an aim of proactively managing patients with frailty.

Process Mapping: An outline of the patient’s journey creating an overview of a service. This is a powerful way for multidisciplinary teams to understand the problems from a patient’s perspective and identify improvement opportunities.15

Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC): Under this care model, patients presenting at hospital with relevant conditions can be rapidly assessed, diagnosed, and treated without being admitted to a ward, and if clinically safe to do so, will go home the same day their care is provided.16

Standard Operating Procedures (SOP): A method to provide clear directions and detailed instructions about how to perform a specific task or process consistently. SOPs aim to achieve uniformity, reduce miscommunication, and adhere to regulatory standards.

Statistical Process Control (SPC) Chart: An analytical technique to plot data over time. It helps to understand variation and doing so guides the most appropriate intervention.17

Resources

Useful resources for those wishing to set up front door frailty services include:

- BGS Frailty Hub

www.bgs.org.uk/FrailtyHub

- BGS Blueprint

www.bgs.org.uk/Blueprint

- BGS Frailty e-learning

www.bgs.org.uk/elearning/2023-frailty-identification-and-interventions

- NHS England frailty resources

www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/older-people/frailty/frailty…

- Acute Frailty Network (AFN )

www.acutefrailtynetwork.org.uk

- GIRFT and BGS: Six Steps to better care for older people in hospital

www.bgs.org.uk/sixsteps

- Improvement Hub Scotland

https://ihub.scot/project-toolkits/frailty-improvement-programme/frailt…

Case studies

Case study one: Queen Elizabeth University Hospital

Phase 1 of frailty at the front doorQueen Elizabeth University Hospital, NHS Greater Glasgow and ClydeIn a four day trial period of a front door frailty service at Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, 122 patients were reviewed by the frailty team with 37% discharged within 48 hours. The team aimed to increase discharges from the ground floor (front door) from 15% to 25%. They achieved an increase to 30%. More information about the trial and next steps can be found at: https://ihub.scot/media/9172/20210507-ihub-case-study-frailty-qeuh-v010… |

Case study two: Swansea Bay

CWTCH interventionSwansea BayThe CWTCH intervention is intended to support care home teams to know when a patient who has fallen can be moved safely and when they should be conveyed to hospital. This aims to reduce the harm caused when a patient is on the floor for a prolonged length of time and avoid unnecessary hospital admissions. CWTCH stands for:

More information can be found at: https://sbuhb.nhs.wales/news/swansea-bay-health-news/a-cwtch-is-helping… |

Case study three: Hereford Hospital

Hereford HospitalWye ValleyWe opened the Frailty Same Day Emergency Care (FSDEC) unit on the 13 September 2023 in Hereford County Hospital. We had a well-established front door frailty team consisting of advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs), but the new six bedded assessment area gave us the opportunity to work from a base and provide a suitable environment for appropriate patients. The majority of patients are pulled from the emergency department, ensuring that we optimise workflow and capacity. At the time of writing we have been open three weeks and seen over 150 patients on the unit and outreached to around 50 more. It has been revolutionary to establish an area next to the emergency department dedicated to the assessment and treatment of older people. Around two thirds of patients are discharged, and for those admitted we ensure referral to the most appropriate acute medical ward. We also have access to community rehabilitation hospitals for patients for whom this is more appropriate. We have tried to set a goal of every patient we treat leaving in a better condition than when they arrived, by managing their acute presentation alongside chronic disease management, identifying frailty, appropriate prescribing and referral and signposting to community services. Moving forward, we are considering how we can best balance ensuring patients receive a thorough multidisciplinary assessment against ensuring flow through the unit, aiming to add value with every patient interaction. The major positive of the experience has been the feedback; patients and their relatives are so grateful of being cared for in a dedicated unit. With regular staff huddles and input from the improvement team, we have been able to use data gathered to best ensure that the unit runs effectively. I have also been encouraged by the level of support from the senior management team. As we were getting started we have been allowed space and time to establish how we work as a team and define how we operate as a unit. - Dr Richard Gilpin, Consultant Geriatrician, Hereford County Hospital At Wye Valley Trust we have opened a six-patient Frailty SDEC Unit next to our Emergency Department. The aim of this is to create a space and environment that is more suitable for older people with frailty, with clinicians and nursing staff who have extended knowledge and interest in care of the older person. The majority of our patients were ‘pulled’ from ED with a smaller number accessing the service direct from the community via referral. We initially drafted patient criteria so that patients could be ‘pushed’ into FSDEC but we soon learnt that the ‘pull’ approach enabled us to select patients more appropriate for an SDEC pathway. We all agreed that if FSDEC was to be effective then good flow would be essential. To protect flow, we would need to prioritise patients that had a high likelihood of being discharged back to their place of residence either with or without involvement of community teams. Similarly, we would want to minimise the number of patients who were likely to need admission either because they were too acutely unwell to be discharged or because they required additional input within their social setting. We didn’t want the time that older people with frailty spent in FSDEC to cause them to become deconditioned and instead wanted to create an environment conducive with supporting their discharge and protecting their independence. We deliberately limited our trolley spaces to two and chair spaces to four. The environment is quiet, friendly and calm. Patients are encouraged by the frailty nurses to be as independent as possible and families are welcome to visit freely. The chairs are arranged to encourage social interaction both between patients and with our staff team. Having a geriatrician presence within FSDEC has proven hugely beneficial for both patients and the ACP team. Ad hoc training sessions have become commonplace alongside more formal weekly sessions of teaching to address various topics relating to frailty. This combined with bi-weekly FSDEC MDT update meetings has meant that we are continuously evaluating our performance and discussing any improvements we need to action. As a trainee ACP, for me this whole experience has been wholly positive so far. The patients I see are full of praise for our service and we have received some fantastic feedback. It certainly feels like a responsive solution to reduce the number of older patients with frailty experiencing long delays in ED. - Sophie Whittall, Trainee Advanced Clinical Practitioner, Hereford County Hospital |

Case study four: Ayrshire and Arran

Frail Older Persons Pathway (FOPP)Ayrshire and ArranThe FOPP Team at NHS Ayrshire and Arran includes representatives from Elderly Mental Health Liaison and Pharmacy, an Allied Health Professional from the community-based Intermediate Care and Enablement Services (IC&ES) Team, an Advanced Nurse Practitioner and admin support. Where appropriate, patients can be admitted directly to specialty beds, including step-down beds in the community, or discharged home with IC&ES follow-up if required. The Team adopts a ‘nothing about me, without me’ philosophy, and carers and family members are actively involved in assessment and treatment decisions. Results have shown an increased use of alternatives to hospital admission, and reduced length of stay for those who are admitted; increasingly direct moves to specialty areas; improved patient flow within both the ED and the wider hospital, and not just for the over-65s. Further details about the service can be found at: https://ayrshirehealth.wordpress.com/2014/08/13/teamhappy-by-rowan_wall…. |

References

Click to expand

- Whitty C, 2023. Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2023, Health in an Ageing Society. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annua… (accessed 16 November 2023)

- British Geriatrics Society, 2014. Fit For Frailty Part 1. Available at: https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018… (accessed 16 November 2023)

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO and Rockwood K, 2013. ‘Frailty in elderly people’, Lancet, Mar 2, 381(9868):752-62.

- Han L, Clegg A, Doran T and Fraser L, 2019. ‘The impact of frailty on healthcare resource use: a longitudinal analysis using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink in England.’ Age and Ageing, Sep 1;48(5):665-671

- Conroy S and Dowsing T, 2013. ‘The ability of frailty to predict outcomes in older people attending an acute medical unit.’ Acute Medicine, 2 (3): 74-6.

- Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, Keeble E, Smith P, Ariti C, Arora S, Street A, Parker S, Roberts HC, Bardsley M and Conroy S, 2018. ‘Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study.’ Lancet, May 5, 391: 1775-82.

- British Geriatrics Society, 2021. Silver Book II: Quality care for older people with urgent care needs. Available at: https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/resource-series/silver-book-ii (accessed 16 November 2023)

- Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, O’Neill D and Langhorne P, 2011. ‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.’ BMJ, Oct 27, 343.

- NHS England, 2023. Delivery plan for recovering urgent and emergency care services. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/delivery-plan-for-recovering-urg… (accessed 16 November 2023)

- Getting It Right First Time and British Geriatrics Society, 2023. Six steps to better care for older people in acute hospitals. Available at: https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/six-steps-to-better-care-for-olde… (accessed 16 November 2023)

- Knight T, Atkin C, Kamwa V, Cooksley T, Subbe C, Holland M, Sapey E and Lasserson D, 2023. ‘The impact of frailty and geriatric syndromes on metrics of acute care performance: results of a national day of care survey.’ Lancet. eClinicalMedicine 102278

- Rubenstein LZ, Stuck AE, Siu AL and Wieland D, 1991. “Impacts of geriatric evaluation and management programs on defined outcomes: overview of the evidence,” J Am Geriatr Soc, p. 39(9 Pt 2):8S–16S; discussion 17S–18S.

- NHS England, 2010. Online Library of Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools; Driver Diagrams. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/qsir-driver-diagr… (accessed 16 November 2023).

- Xue Q, 2011. The frailty syndrome: definition and national history, Clin Geriatr Med, Feb 1, 27(1): 1-15

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2005. Process mapping, analysis and redesign. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/… (accessed 16 November 2023).

- NHS England, undated. Same Day Emergency Care. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/urgent-emergency-care/same-day-emergency-car… (accessed 16 November 2023).

- NHS England, undated. Statistical process control tool. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistical-process-control-tool/ (accessed 16 November 2023).