Non-specific presentations

Weakness, fatigue, as well as impaired mobility are among the most frequently reported symptoms in emergency departments.141

In contrast to specific complaints such as chest pain, which can be caused by a small number of diseases (e.g. the so–called ‘big five’ in chest pain), Non-Specific Complaints (NSCs) can be caused by numerous underlying conditions, the interaction between these and/or associated polypharmacy.142

Previously, NSCs were defined as all complaints that are not part of the set of specific complaints or signs or where an initial working diagnosis cannot be definitively established.143 However, the classification of complaints as ‘non-specific’ is subjective and depends on physician related factors such as clinical experience, training, and the setting. Patient-related factors include the patient’s ability to articulate symptoms, cognitive status and physiology.

Non-specific presentations, which are specific for older people with frailty, challenge models of care that are based on single system problems. Traditional signs and symptoms of illness can less obvious (or are less frequent) in older people with frailty. Therefore, acute illness can present with non-specific signs and symptoms such as functional decline or weakness in older adults with frailty. For example, respiratory and non-respiratory symptoms are less commonly reported by older patients with pneumonia (in 20% they do not complain of cough, in 35% neither dyspnoea nor sputum was reported, in 50% no fever, in 60% no tachycardia).144 On the other hand, clinicians frequently use the presence of NSCs to diagnose and ‘empirically’ treat infection, despite the absence of classic signs and symptoms. However in a recent study, non-specific symptoms of malaise and lethargy did not substantially increase the probability of bacterial infection being present in older adults, probably because of the high prevalence of NSCs through the entire ED population and the broad range of potential differential diagnoses.98,142 Therefore, NSCs should not be used alone to diagnose infection.

Instead, the clinician needs to consider complexity and risk of adverse outcomes. When managing patients with NSCs in the ED it should be considered that they are often difficult to discern, often have several underlying precipitating factors,142 and that recovery might be more prolonged and possibly incomplete. Patients presenting to the ED with NSCs belong to a high-risk group, but often receive low triage priority despite a three-fold increased risk of in-hospital death compared to patients with specific complaints.145 Furthermore, the clinician should interpret vital signs in the light of altered physiology. For example, fever of 38C or higher is associated with moderate to large increases in probability of bacterial infection,98 but the absence of fever does not rule out infection. In older patients with a suspected infection, the threshold of systolic blood pressure (>100 mmHg) which is considered ‘normal’, is not helpful for risk stratification of older ED patients with a suspected infection - comparison with baseline vital signs is essential.146

It is important to avoid ageist language; ‘acopia' and 'social admission' are not diagnoses.147 Unfortunately, such ageist terms are frequently used to describe older patients who present to the ED with NSCs. However, it should be considered that patients labelled as having ‘acopia’ have substantial morbidity and a mortality rate as high as 22%.148

|

Resources: Non-specific presentations |

Dementia

Older adults with dementia in urgent care settings are at increased risk of poor health outcomes and high healthcare costs compared to their cognitively normal peers. They tend to incur lengthier ED visits, higher rates of potentially burdensome and invasive testing or imaging, higher rates of hospital admission and readmission, and death.91,149,150

| Mind | Knowledge of baseline cognitive function is essential in evaluation of acute changes; baseline presence and severity of behavioural symptoms of dementia; presence of substance use and abuse; availability of community and caregiver support and degree of caregiver burden or burnout. |

| Multicomplexity | Medical comorbidities and geriatric syndromes (frailty, falls, incontinence, skin breakdown); comprehensive physical examination; maintaining a broad differential. |

| Medication | Thorough review of accurate medication list with focus on psychoactive medications (anticholinergics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotics) and recent changes including new or discontinued medications and dose adjustments; medication adherence – is administration supervised and reliable; be prepared to stop unnecessary or potentially harmful medications. |

| Mobility | Understanding of baseline mobility/self-care ability and acuity of changes; safety and accessibility of home environment and availability of caregiver support; access to transportation for follow-up care. |

| Matters Most | Patients with dementia may no longer be able to participate in or direct their care; dementia is an incurable disease with limited life expectancy - quality of life and burdens of treatment should be considered when developing plan of care; collaboration with the designated health care agent and/or review of advance directives should be made to determine the type of care that the patient would seek to receive and forego in case of serious life-threatening illness. |

Despite higher rates of hospital admission, many patients with dementia may be discharged sooner than is often the case. Engage a caregiver who does not have cognitive impairment and provide straightforward oral and written information regarding treatment plan and warning signs that should prompt an urgent follow-up.152 Communicate with the primary care provider to ensure that the patient has appropriate follow-up. Involve social workers in determining eligibility and making referrals to community based support services or dementia-care programmes.

|

Resources: Dementia in urgent care |

Delirium

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention and awareness that is accompanied by an acute loss in cognition and cannot be better accounted for by a pre-existing or evolving dementia.

153This form of acute brain failure affects 8% to 17% of older Emergency Department (ED) patients

154,155 and is associated with accelerated cognitive and functional decline 156 and higher mortality. 157 Unfortunately, ED healthcare providers miss delirium in 67% of cases. 158Delirium can vary by psychomotor activity with important clinical implications. Patients with hypoactive delirium may appear drowsy, somnolent, or lethargic. Patients with hyperactive delirium appear restless, anxious, agitated, or combative. Patients with mixed-type delirium exhibit both hypoactive and hyperactive symptomatology. Hypoactive delirium is the most common subtype and carries the worst prognosis but is often unrecognised by healthcare providers.

159 Hyperactive delirium is the least common subtype and is not associated with adverse outcomes but usually recognised.To improve delirium recognition, urgent care services need to actively look for this syndrome. Delirium assessments such as the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM),

160 Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) 161 and the 4AT 162 have been validated in older ED patients. These assessments take 1 to 2 minutes to perform and require the rater to administer brief bedside cognitive testing to the patient. Ultra-brief (<30 seconds) delirium assessments exist such as the months of the year backwards task 163 and Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS). 164 In general, these ultra-brief delirium assessments have decreased diagnostic accuracy compared with the bCAM, CAM-ICU, and 4AT.Once delirium is detected, the ED’s primary objective is to diagnose and treat the underlying cause. This requires comprehensive and careful evaluation. Because patients with delirium are less likely to provide an accurate history, any history should be obtained or confirmed from a collateral source such as a family member or caregiver. Obtaining accurate medication (prescription and over the counter) and substance abuse histories are also critical because adverse drug reactions and drug withdrawal are frequent delirium precipitants, respectively. A complete head-to-toe examination should be performed. The physical examination should include a thorough ocular (nystagmus, pupils), neurologic (focal motor weakness), genitourinary (infected decubitus ulcers or perirectal abscess), and skin (drug patches or infections) exams.

Laboratory and radiographic testing are routinely performed as part of the evaluation. Because Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) are common precipitants of delirium, urinalyses are often obtained. However, special caution must be taken in their interpretation, because a significant proportion of older adults have Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, which may not necessarily be the cause of their delirium.

165 In addition, the majority of older ED patients with delirium will have more than one cause present, 166 even if UTI is suspected other causes for delirium should still be considered.Delirious patients can become easily agitated in the ED environment, because of perceptual disturbances and difficulty verbalising distress. Every effort should be taken to minimise ED interventions that can potentially precipitate or exacerbate agitation. Pain should be promptly addressed using non-opioid and opioid pharmacological agents. Tethers such as nasal oxygen cannulae, multiple intravenous lines, and monitoring devices can trigger or exacerbate agitation, and should only be used when absolutely necessary. Urinary catheters should be avoided because they are particularly noxious and fraught with complications such as catheter-associated infections.

|

Resources: Delirium in the urgent care setting |

Managing challenging behaviour

Challenging behaviour refers to a range of disruptive and culturally inappropriate behaviours including disinhibition, agitation and verbal and physical aggression and may be a result of a range of mental disorders and/or intoxication.

When manifested in older people in an emergency care setting, such behaviours, particularly in the form of physical aggression, pose an obvious risk of harm to the patients concerned and to those around them. A recent systematic review167 of studies of aggression risk found a five-fold increase amongst people living with Alzheimer's dementia compared with healthy older people but no increase in risk among people with mild cognitive impairment. A large national survey of violence in mental healthcare settings168 indicated that physical assaults on staff were most frequently encountered with older patients having organic mental disorders. The frailty of the patients did not prevent serious injuries being inflicted. These incidents occurred despite the staff involved being skilled at using person-centred approaches to maximise dignity and good compliance with standards for privacy and choice.

All clinical staff working in EDs need to be aware of the conditions which may be associated with challenging behaviour and be competent to recognise signs of behavioural escalation. Whilst non-pharmacological interventions and de-escalation techniques should always be tried where possible, situations will inevitably arise in emergency care settings where drug treatments in the form of rapid tranquillisation will be needed to protect staff and other patients from acts of aggression and/or to facilitate adequate assessments of individual’s physical health. Evidence-based guidance on the short-term management of disturbed behaviour by psychiatric patients in EDs has been issued by the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.169 Acutely older people will not always be able to articulate the reasons for their distress and it is always important to establish whether pain, constipation, urinary retention or psychosis underlie the disturbed behaviour. The NICE guideline gives helpful advice on recognising situations which may progress to violence and how to avert this. Medication should only be used where it is the safest and least restrictive way of managing behaviour, which poses a serious risk to other patients, the staff or other people in the urgent care setting, or to patients themselves. A lack of international consensus on the optimal drugs to use in these circumstances has been acknowledged in a recent review.170 In most countries best practice will align with either a short-acting benzodiazepine or a low dose of an antipsychotic tranquilliser such as haloperidol. The treating team must be fully cognisant of the adverse effect profile of the selected drug in each particular patient, and observe basic principles such as using the minimum possible dose. There is no evidence that larger doses are more rapidly effective than smaller doses.

|

Resources: Managing challenging behaviour

|

Depression and self-harm

Depression is the most common mental health problem in later life and has an important and bi-directional association with physical ill-health.

Older people with a wide range of acute and chronic physical disorders experience increased rates of depression, and physically ill older adults with comorbid depression experience worse health outcomes and increased utilisation of healthcare resources. Depression is especially prevalent in older acute hospital inpatients (29%)171 and older emergency department attenders (32%).172 Despite being an important problem in its own right and a complicating factor in the management of other conditions, for some time there has been evidence that the recognition of depression in these patients in emergency departments is suboptimal.173 There is persisting evidence that many opportunities for the diagnosis and treatment of depression whilst older adults are in hospital continue to be missed.174

Of all of the risks associated with depression, the gravest is that of deliberate self-harm and suicide. Self-harm in older people is much less common than at a younger age; of 5038 consecutive self-harm attendances in one Emergency Department, 110 (2.2%) were of people aged 65 years or over.175 However older people who self-harm have high levels of suicidal intent176,177 and often have on-going suicidal ideation following initial presentation. World Health Organisation data indicate that between a quarter and half of all suicides are accounted for by people aged 55 or over with considerable variation between countries. Among older adults there is a much stronger association between self-harm or completed suicide and mental health problems than in adults of working age. About 15% of older people with a first episode of self-harm go on to repeat the act, and there is a 49-fold increase in risk of suicide.177

Clinicians working in urgent care need to be aware of the high prevalence of depression and appreciate its significance to the management of any physical presenting problems and the risks that may arise directly from depression, especially suicide and deliberate self-harm. Consideration could be given to the use of brief screening instruments such as the 4-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale that has sensitivity approaching that of the well-known 15-item version of the scale,178 the latter being too lengthy for routine use in urgent care settings. Although the context may be different, evidence indicates that the phenomenology of old-age depression in far more similar than it is different to depression in younger adults. The presence of suicidal ideation should always be fully explored in patients presenting to urgent care settings with depressive symptoms or following an episode of self-harm; clinicians need to be aware that talking about suicide will not increase the likelihood of it occurring.

Depending on the local service configurations, patients with less severe depressive symptoms may be identified for further assessment and treatment either by their family physician or directed towards a community mental health team once they have left hospital. These referral pathways need to be clear and well-understood. Those patients with suicidal ideation or symptom severity sufficient to impact their treatment in hospital or their discharge planning require timely referral to, and assessment by, a specialist mental health clinician who is competent to undertake psychosocial assessments in older patients. A minority of severely depressed and suicidal patients will require transfer to a mental health in-patient unit once their physical status is stabilised.

An example of an evidence-based framework for delivering optimal acute care to patients of all ages who have self-harmed is contained in The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (England) guidance CG16. The associated interactive flowcharts may assist with care pathway design and the embedded quality statements may be used as a basis for an assurance framework.

Substance use

Across health and social service systems, increasing numbers and proportions of older adults will present with a range of alcohol and drug use.

'Baby Boomers', the generation who began turning 65 in 2011, have witnessed more permissive attitudes towards drugs and alcohol than previous generations. Prevalence rates of the three most commonly used substances by adults 50 and older - alcohol, cannabis, and non-prescription medications - are increasing. For example, since 2005, adults 50 and older demonstrated 23% increase in alcohol use disorder, and adults 65 and older demonstrated a 250% increase in past year cannabis use179,180 for both recreational and medicinal reasons. US national data from 2017 reveal that over 10% of adults 65 and older are binge drinkers. Among older adults with frailty, over use of prescription medication, such as sedatives or opioids, for sleep or pain is also common, and use of opioids with suicidal intent has been increasing in last decade.181

Older adults tend to avoid disclosing any substance use, either due to shame or attribution of health problems to ageing - contributing to an ongoing, invisible, public health problem. While not all substance use is harmful to older adults, age-related changes in the body and brain may increase vulnerability to the negative effects of substances, even when use in moderation. Older adults may not realise that maintaining substance use levels from middle age into late life can begin to cause new problems. For some older adults, any substance use may be problematic due to interactions with prescribed medications or comorbidities.

Healthcare and social service providers will be increasingly expected to assess older adults for substance use and related problems, and refer to appropriate care. While many providers may hesitate to ask older adults about substances, due to a fear of offending them or because they do not believe it is likely to be relevant, direct questions are necessary. Like most people, older adults respond best to an empathic, non-confrontational approach.182 Use of open-ended questions and reflections that normalise substance use will likely yield the most information and provide the best means of engaging in a conversation, providing a solid foundation for assessment and/or intervention.

Potential signs of substance use or abuse requiring further assessment are, among others: increased tolerance to medications, chronic pain, headaches, falls, running out of medication early, recent difficulties with decision making, declines in functioning, cognitive impairment, mood swings, and sleep disturbance.183 Given these symptoms are shared by other medical and psychiatric conditions, substance use is often masked or mistaken for something else, including normal ageing. At times, a more comprehensive person-in-environment assessment will be required. For example, a son noticed his father, who suffered with Alzheimer’s disease, had increased his drinking from one to six beers each night, based on bottles found in the recycling bin. When the son investigated further, he discovered that his father’s short-term memory problems impaired his ability to remember he had already had his nightly beer (a habit continued from middle age), and thus kept drinking one more beer.

While some substances may be tested for in a blood or urine panel, there are also a number of psychosocial screening tools that can be used with older adults to assess for substance use.184 Some tools perform better than others (e.g. the full Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test is insensitive with older adults, while the AUDIT-5 performs much better),185 and tools’ reliability, validity, and specificity may vary across countries and cultures. A comprehensive assessment of older adult’s use of substances including prescription and non-prescription medications, alcohol use and other substances, including cannabis, can help detect unhealthy use and prevent harm through development and execution of an appropriate care plan.

|

Resources: Substance abuse and mental health

|

Falls and syncope

Fall-related injuries are a leading cause of morbidity, mortality and a major public health issue. Fall-related deaths account for up to 40% of all injury deaths worldwide.188 The Emergency Department (ED) is often the first place where patients with fall-related injuries seek medical care - falls account for 17% of all ED presentations in older people.189

The ED evaluation for older people who present to ED after a fall should include:

- Diagnosis and treatment of traumatic injuries

- Finding out and managing the causes or predisposing factors of the fall;

- Preventing complications of falling and future falls

Most falls in older people are multifactorial, and akin to the cumulative deficit model proposed for other geriatric syndromes. In the acute care setting, it is important to look for the immediate medical life threats presenting as syncopal falls, such as rapid GI blood loss or pulmonary embolism. However most falls seen in ED will be a complex interplay between chronic intrinsic factors that make a person more prone to falling and the extrinsic environment. Some potentially modifiable factors commonly overlooked by the acute/urgent care physician include orthostatic hypotension, uncorrected visual disturbance, chronic postural instability, and perceptual disturbance related to psychoactive medication use or alcohol.

Because of the time-consuming nature of full fall evaluations and multifactorial fall risks, the evidence shows a low rate of adherence to comprehensive guidelines such as the Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP).84 One suggested approach is to manage falls assessment along a timeline (see Table 1, below), with initial time critical assessment in the ED and a longer assessment period in a short stay ward or frailty unit.

|

Timeline |

Risks |

Examples of evaluation enablers |

|

Initial assessment |

Acute medical illness associated with fall |

ECG, septic screen, orthostatic vital signs, fluid balance assessment |

|

Acute injury e.g. hip and back, face/head/neck, ribs |

Xrays. Consider neuroimaging if indicated by Canadian CT rules |

|

|

Within 3-4 hours |

Cognitive impairment including delirium |

4AT/CAM |

|

Gait and balance disturbance |

Current mobility, need for aids, feet and footwear assessment |

|

|

Discharge risk stratify |

Home safety, escalation plan if falls again |

|

|

Within 24-48 hours

|

Bladder and bowel incontinence |

Generally requires multidisciplinary assessment e.g.

|

|

Functional decline and frailty, malnutrition |

||

|

Home environment modifications |

||

|

Depression |

||

|

Hearing and vision |

||

|

Medication review |

A multidisciplinary safety assessment before discharge should be routine in patients presenting with an acute fall, or those that have had two or more prior falls in the last twelve months. There are a number of RCTs that have evaluated the effectiveness of multi-factorial secondary falls prevention programs. The Prevention of Falls in the Elderly Trial190 found a reduction in recurrent falls by providing multi-factorial interventions with twelve months' follow-up. A second telephone-based, patient-centred intervention study in Australia,191 found a reduction in falls but not fall-related injuries following six months telephone-based education, coaching, goal setting, and support. However there have been many other negative studies and intervention in cognitively impaired patients who presented to ED with falls showed no significant reduction in falls during 1-year follow-up.192

|

Resources: Falls assessment in urgent care settings |

Silver trauma

The nature of major trauma is changing,193 and now forms two distinct syndromes. In the developed world traditional ‘high energy transfer’ major trauma (young, male, road traffic collision) has become the minority, as ‘low energy transfer’ major trauma (older, female, fall on one level) has become more common.194

The older major trauma patients are just as seriously injured as younger patients, but they are not identified by the prehospital trauma triage tools and are difficult to identify in the Emergency Department.195 This means that older major trauma patients don’t have direct transfer to a Major Trauma Centre, don't have a trauma team response in the ED, are looked after by more junior staff, have delayed investigations (such as CT), and delayed intervention. Major trauma systems are set up to optimise treatment for ‘high energy transfer’ major trauma, so may not be appropriate for major trauma in older patients.

The commonest severe injuries in older people are to the head and chest. These severe injuries are often ‘stealth trauma’196 so not immediately recognised, with an underlying theme that the focus of clinical care is on the associated intercurrent acute medical illness. It may not be in the best interests of every older person to be immediately transferred to a major trauma centre (as few will require intervention), but for every patient there is the requirement for urgent multi-speciality and multi-disciplinary decision making:

- Staff education about: (a) awareness of the potential for a ‘needle in the haystack’ of major trauma in older fallers patients, (b) that older people often do not complain of ‘pain’ (‘ache’ or ‘uncomfortable’ are commoner terms)

- Trauma primary and secondary surveys for every older patient who has a fall

- Low threshold for whole body CT scanning, particularly for any patient with chest discomfort following a fall

- Procedures in place for activation of rapid multi-specialty trauma care advice following late identification of severe injury (in the emergency department or on a medical ward) without transfer to Major Trauma Centre.

- Multi-disciplinary management of chest injury

- Inclusion of major trauma in geriatric training curricula (the word ‘trauma’ does not occur in either the American or Australasian training curricula and the two occurrences in the UK curriculum both only relate to management of medical comorbidities)

- Use a trauma record sheet for every older faller, even if no overt signs of injury, to force a trauma secondary survey

- Inclusion of geriatric trauma as a specific category in local radiology guidance.197

- Trauma centres taking responsibility for providing remote multi-specialist trauma advice and assistance in decision making to every hospital within the catchment area. A system in every hospital for access to this major trauma specialist advice

- Development and implementation of local chest injury management bundles specific to the needs of older patients.198-200

|

Resources: Silver Trauma |

Fractures and secondary prevention

Osteoporosis-related fractures represent a major health care problem demanding immediate attention from a physician. It is estimated that one in three women and one in five men aged 50 years or older will sustain a fracture in their lifetime.

All types of fractures are associated with increased morbidity and mortality and with decreased quality of life leading to personal, societal and economic impact.104,201,202

Unfortunately, the number of patients who do not receive adequate attention after a recent fragility fracture remains alarming.203 Post-fracture care includes a number of facets ideally bundled in a Fracture Liaison Service (FLS), a multidisciplinary care trajectory offering screening as well as treatment for osteoporosis. Screening includes the measurement of Bone Mineral Density (BMD) using Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA), and evaluation for possible underlying secondary factors for increased fracture risk with laboratory investigations in fragility fracture patients.

Establishment of a FLS is associated with a decrease in the incidence of new fractures and in mortality.204 This approach has thus proven to be a successful formula in the management of osteoporosis by providing secondary fracture prevention in patients with a recent fracture in a cost-effective approach.205

To improve the initation of fracture prevention, patients need to be aware of their increased fracture risk. Although a complete fracture risk assessment is not necessary in the urgent care context, a standard general risk assessment can be performed by using the FRAX algorithm. FRAX is a computer-based algorithm that is accessible online and makes use of the presence or absence of independent risk factors to generate a 10-year probability for a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical spine, hip, distal radius and humerus) and for a hip fracture.206 The model input includes an individual’s age, gender and BMI, and information on the presence or absence of the following risk factors: prior fracture, parental history of hip fracture, ever use of glucocorticoids, current smoking, excessive use of alcohol, rheumatoid arthritis and other secondary causes for osteoporosis. Fracture risk prediction has been shown to be improved by including data on femoral neck BMD in the calculation although FRAX can also provide fracture risk prediction without the inclusion of BMD.207 FRAX calculation only takes 1-2 minutes and can be performed by a nurse. However, the FRAX calculator does not take into account risk factors such as the presence of morphometric vertebral fractures, falls and frailty.206 Therefore in frequent fallers, defined as ≥2 falls in the past year, the Garvan calculator could be used. The Garvan calculator takes less than 1 minute and can also be filled in by a nurse. Similar to FRAX it also provides a 10-years risk on major osteoporotic fractures as well as hip fractures, and additionally provides a 5-year probability for a fracture. These calculated fracture risk probabilities can directly be communicated to the patient and caregivers to emaphasize the importance of the future appointment at the FLS as it has been shown that patient education increases FLS attendance.

Laboratory testing solely for fracture risk assessment should not be performed in the urgent care setting, however if blood is drawn for pre-surgical screening or other indications, it might be reasonable to extend the screening by including Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, corrected calcium, phosphate and creatinine. The measurement of markers of bone turnover will not be of use considering the recent fracture.

When X-rays of the chest or CT scans of the thorax or abdomen are performed attention should be given to the detection of vertebral fractures. Vertebral fractures are one of the most common complications of osteoporosis but are often missed or omitted from the conclusion of the radiological report.208 The presence and grade of severity of vertebral fractures however are predictive for the risk of new vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, independently of BMD measurements.209

However, the most important action in the urgent care context is to explain the patient and caregivers that their bone fragility should be evaluated by a Fracture Liaison Service or General Practitioner in order to reduce the risk of future fractures.

|

Resources: Osteoperosis |

Pain

Pain in the older adult population is very common, particularly in urgent settings. It is important to be able to recognise pain, diagnose underlying conditions that might be causing it, and adequately treat it in order to maximise function and quality of life.

Older adults are more likely to have cognitive impairment, which confounds pain assessment. They often have different kinds of pain simultaneously, increasing diagnostic uncertainty. They also have age-related physiological changes, comorbidities and chronic conditions that affect the way pain medications are absorbed, distributed, metabolised and excreted. All of these make older adults more prone to adverse effects of these medications.

Concurrently, clinician fear of adverse effects can lead to under-treatment or untreated pain for these vulnerable patients, which place patients at risk for other sequelae including delirium, disability, and risk of developing chronic pain. It is crucial that assessment and treatment of pain is undertaken routinely for all older adult patients regardless of the setting. The key steps are summarised below and suggested analgesia outlined in the following table.

- Initial pain assessment and frequent reassessment are crucial to optimal pain management.

- If cognitively intact: self-reporting with use of validated tools like the 0-10 scale (Numeric Rating Scale)210 or FACES pain scale211

- If cognitively impaired: attempt self-report and change from baseline, review of painful conditions, evaluation of pain behaviours (validated tools include PAINAD,212 PACSLAC-II,213 Abbey pain scale214) caregiver report, and if necessary empirical analgesic trial

- Awareness of renal, cardiac function and gastrointestinal comorbidities are important in determining choice of therapy.

| First line treatments | Adjuncts |

| Acetaminophen / Paracetamol First line therapy regardless of severity of pain, safe in all patients except for those with liver impairment or those weighing less than 50kg (in which case dose should be reduced). Suggest generally using no more than 3000 mg in a 24-hour period, can be given every 8 hours at 1000 mg/dose for ease of administration. Can be used alone or in conjunction with other medications. |

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) Systemic NSAIDs (i.e. ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac) are generally avoided due to risk of renal injury, GI irritation, and cardiovascular effects. However, they can be used for short-term treatment (limited course over a few days) in those with no immediate contraindications. These may be particularly useful for acute, inflammatory/arthritic pain that is expected to improve in a short period of time, such as gout. |

| Topical treatments Largely safe to use and may be combined with oral therapy, though efficacy is limited. Suggest capsaicin patches, topical lidocaine and topical NSAID therapy as available. |

|

| Opioids Can be used to treat moderate-severe pain. For opioid-naïve patients, start at the lowest dose possible, using longer dosing intervals and titrating slowly based on response. Choice of opioid depends primarily on presence of renal impairment and desired timing of pain relief. If renal impairment is present, avoid morphine and use oral oxycodone (suggested starting dose 2.5-5mg every 6 hours as needed) or oral or parenteral (intravenous preferred over intramuscular) hydromorphone. If renal function is normal, any can be used but may choose to start with morphine given its lower cost. Parenteral administration works faster than oral and may be an ideal choice for the patient in urgent/emergent settings to achieve pain relief. |

Neuropathic agents

Can be considered for pain that is primarily thought to be neuropathic. Gabapentin is often used first line due to its quick onset of action. Suggest starting with low dose at night (i.e. 100 mg) and slowly up-titrate. Dose must be adjusted in the presence of renal impairment.

|

| Steroid injections

Particularly useful for focal joint pain; minimal systemic side-effects. Requires a trained professional to administer and efficacy varies.

|

|

| Non-pharmacologic approaches

Increasingly are found to have added benefit and should be routinely incorporated, especially in cases of chronic pain. For acute pain management, non-pharmacological options include nerve blocks, acupressure, reflexology, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

|

Polypharmacy and appropriate prescribing/deprescribing

Polypharmacy can be defined either based on the concurrent use of multiple medications or the administration of unnecessary medications.

The second definition of polypharmacy considers medication appropriateness during medication review. A medication is considered as unnecessary if the medication lacks an indication or efficacy or a therapeutic duplication. Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medications (PIMs) have been associated in studies with reduced quality of life, Adverse Drug Events (ADEs), falls, non-adherence, hospitalisation, mortality and increased healthcare utilisation and cost.216

Polypharmacy may be related to ‘prescribing cascade’, a term refers to additional medication is prescribed to treat an adverse effect of another medication. In this scenario, a provider misses that the patient’s new symptom is the result of a current medication, prescribing a new medication to treat instead of recognising and stopping the causative medication, increasing the risk of side effects and ADEs.

Both explicit (criterion-based) or implicit (judgement-based) processes may be used to assess the appropriateness of medications. The explicit process creates a list of medications that are to be avoided among older adults through expert consensus, such as the Beers Criteri217 and STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment).218,219

The implicit process requires clinicians to review the appropriateness of a patient’s medication regimen with the help of a data collection tool, such as Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI). The MAI establishes the appropriateness per drug based on its indication, effectiveness, duplications, correct and practical directions, drug-drug and drug-disease interactions, dosage, duration, and cost.220 An important consideration is to assess Anticholinergic Burden, especially in older people with cognitive impairment (delirium and/or dementia).

Appropriate prescribing requires a Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) approach. Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practice for Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED) is an example of ongoing, multisite quality initiative in the United States that aims to decrease inappropriate prescribing in the ED. The EQUiPPED intervention consists of provider education though physician-pharmacist academic detailing (a method of clinician engagement that involves one-on-one, clinician-to-clinician interaction to help ED providers become better informed and equipped to make clinical decisions on medications), clinical decision support, and provider feedback on prescribing practices.

‘Deprescribing’ is another approach to handling unnecessary medication use and polypharmacy. Deprescribing is the process of tapering, stopping, discontinuing, or withdrawing drugs, with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes. Deprescribing is proposed to comprise five steps:

- Ascertain all drugs the patient is currently taking and the reasons for each one

- Consider overall risk of drug-induced harm in individual patients in determining the required intensity of deprescribing intervention

- Assess each drug in regard to its current or future benefit potential compared with current or future harm or burden potential

- Prioritise drugs for discontinuation that have the lowest benefit-harm ratio and lowest likelihood of adverse withdrawal reactions or disease rebound syndromes

- Implement a discontinuation regimen and monitor patients closely for improvement in outcomes or onset of adverse effects.221

|

Resources: Polypharmacy |

Sepsis

Sepsis, defined as a dysregulated host response to infection, in high-income countries is predominantly a disease of older people. Older patients with sepsis have higher levels of potentially reversible organ dysfunction, have higher rates of mortality, and if they survive are more likely to have long-term functional impairment.222

Factors such as comorbidity, immunosenescence and medications mean typical features of a systemic inflammatory response may be less obvious in an older patient with sepsis. Sepsis can present in subtle or non-specific ways such as acute confusion, unexplained fall or functional decline.

Clinicians should consider sepsis in the differential diagnosis of any acutely unwell older adult. Screening can use sepsis risk factors e.g. recent hospitalisation or invasive procedures, chronic disease or medication-related immunosuppression. This is followed by risk assessment of those with features of infection, including attention to vital signs (in particular tachypnoea, altered mental status, relative hypotension) and measurement of serum lactate.223,224

Shock requires resuscitation with intravenous isotonic crystalloid. Studies indicate that older patients are often under-resuscitated, often related to unfounded concerns about the risk of fluid overload. Clinicians should be reassured that in all of the sepsis trials, there were very few reported adverse events including fluid overload. If appropriate, commence a vasopressor infusion if there is an inadequate response to fluid resuscitation.

Features of acute organ dysfunction should prompt treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics directed at the suspected source. Blood cultures (at least two sets) should be obtained, ideally before antibiotics, along with urine and other clinically relevant microbiological samples. Clinicians should consider the need for source-control by removal of infected tissue or invasive devices.

Goals of care need to be established promptly, since sepsis may complicate an underlying life-limiting illness such as malignancy or dementia. Treatment decisions need to be carefully weighed alongside patient goals and values. A realistic appraisal of the benefits and harms of invasive organ support is important to guide expectations in discussions with patients and carers.

Sepsis prevention should not be overlooked. Hospital and aged-care facility acquired infections can be reduced by meticulous attention to measures such as hand hygiene, and at-risk populations should be offered immunisation against pneumococcus and influenza.

| Older adults with suspected sepsis should be assessed in an area equipped with monitoring equipment (ECG, blood pressure, oxygen saturations) and ready availability of laboratory investigations (including blood gas analysis with lactate) and x-rays. |

| A systematic and structured approach to sepsis identification and treatment minimises the chances of missed or delayed diagnosis. |

| Paper-based or electronic ‘sepsis pathways’ incorporate alerts for risk stratification. A number of tools have been promoted to predict risk of deterioration or mortality. In older patients, those incorporating age and comorbidity may be superior to those based solely on acute physiology. |

| A multidisciplinary approach to acute care may require communicating with the general practitioner and any relevant chronic disease specialists. |

| Further online resources available at: https://www.sepsis.org/sepsis-and/aging/ and http://www.survivingsepsis.org/Pages/default.aspx |

Urinary tract infection

Infection in older people is a major issue from patient, healthcare provider and societal perspectives. Assessing older people for possible infection is any everyday occurrence. Misdiagnosis is common, leading to important adverse consequences including death, and can be costly in terms of hospitalisations and antibiotic resistance.

Ruling in or out infection can be especially difficult in older people who often present with ‘atypical’ or non-specific presentations such as delirium or immobility.225 There are problems with over-diagnosis; where there are barriers to communication such as stroke or dementia, signs and symptoms can be far less clear.226 Assessment can be further confounded if there is a urinary catheter in situ (fewer symptoms/signs and colonisation the norm)227. Clinicians might erroneously attribute factors such as functional decline, increased confusion, and other non-specific signs and symptoms to infection, and start treatment on this basis.226,228 Under-diagnosis is also an important risk, as typical clinical markers for infection may not be helpful (e.g. fever is not sensitive or specific for infection229) and biomarkers such as white cell count, C-reactive protein or Interleukin-6 lack sensitivity and specificity in older people.230,231

A specific consideration in the context of Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) is the frequency of Asymptomatic Bacturia, which should not be treated,232,233 but may be misinterpreted as the cause of the presentation. As many as 25% to 50% of older women and 15% to 40% of older men in long-term care facilities have bacteriuria,234 and colonisation of urinary catheters is extremely common.

The complexity surrounding the diagnosis of infection in older people can lead to uncertainty about treatment. Over-treatment risks unnecessary exposure to antibiotics and associated side-effects (e.g. C. difficile infection), as well as adding to antimicrobial resistance, and importantly means that the true explanation for the patient’s presentation might be missed. Under-treatment is associated with the development of sepsis.

Be aware that diagnosing UTI in older people is fraught with clinical risk. Be sure that you have carefully considered the objective evidence for infection, and then specifically the urinary tract as the source. Do not reply upon urine dipstick tests when diagnosing UTI on older people. Think holistically about what might have caused the presentation, other than infection (polypharmacy, metabolic disturbance, pain, constipation, etc).

|

Resources: Urinary Tract Infection

|

Continence

Incontinence in older people is a major concern to older people, their care partners, healthcare systems and to society. Incontinence is not just a 'lifestyle' disease.

Urinary incontinence and associated lower urinary tract symptoms affect up to 1:3 women and 1:12 men >65 years of age respectively. Incontinence is associated with significant comorbidity, including depression, falls and fractures, urinary tract infection, social isolation and deconditioning. Incontinence, particularly urgency incontinence, may be an early marker of incipient frailty and impending institutionalisation.235-237 Faecal incontinence affects up to 17% of older adults, with similar adverse effects upon quality of life.238 Asking older people about continence status in the acute setting is therefore important but is frequently neglected where 'more important' presenting conditions are present; however, to fail to ask may lead to suboptimal outcomes following resolution of the acute illness.

For many older people, incontinence is a stigmatising condition and they will not volunteer the problem; up to two thirds of older women think that incontinence is normal for aging.239 There continues to be a lack of awareness of what might be done to manage incontinence and an assumption that surgery might be required for treatment. Active case finding in order to gain knowledge of how an older person normally manages their toileting needs, and whether they have problems with maintaining continence, is therefore imperative.240

In older people, the underlying causes of urinary incontinence are typically multifactorial and may be elucidated by a careful comprehensive assessment. In the majority of cases, for those with both urinary and faecal incontinence, a clinical history, dietary assessment and symptom evaluation will provide sufficient diagnostic information upon which to base further management. Essentially, as with any geriatric syndrome, comorbidity, polypharmacy, physical and cognitive function as well as lower urinary and gastroenterological tract dysfunction need to be considered when making a plan for treatment. Acute and reversible causes for incontinence need to be identified and treated. A pelvic and rectal examination to search for underlying pathology (symptomatic genitourinary prolapse, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, faecal loading, and assessment of pelvic floor function) is important. Algorithms for assessment and management in older people with frailty have been published by the International Consultation on Incontinence.241

Lifestyle, behavioural and pharmacological management for bladder and bowel dysfunction are available and effective in older people, but evidence for older people with frailty is lacking. Due regard should be given to the expectations of patients and their care partners as well as to the healthcare burden imposed by any proposed intervention when implementing a management plan.

|

Resources: Continence |

Nutrition

Malnutrition is a complex, multidimensional condition that is common among older adults.242 Globally, malnutrition is estimated to affect one in three people with public health and economic productivity costs estimated at $3.5 trillion per year.243

Older adults frequently suffer from malnutrition, due in part to poverty, dental problems, and physical and cognitive disabilities that make it hard to obtain or prepare food. Other factors that contribute to malnutrition among older adults include chronic medical conditions, polypharmacy, lack of transportation, and social isolation.244,245

Emergency Departments (EDs) provide a potentially important setting to address malnutrition because older adults with limited financial resources often have difficulty accessing primary care and so depend on the ED for care.246 The prevalence of malnutrition is estimated to be 12%-16% in the US, and may be higher in other countries.242,244 Achieving the potential of the ED to reduce the burden of malnutrition in older adults will likely require a combination of screening followed by connecting malnourished older adults to long-term solutions such as community-based resources.

Several brief, validated screening tools for malnutrition currently exist including the two-item Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), the six-item Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF), and the three-item Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ).247 The MST is a malnutrition assessment that has been extensively validated in multiple patient populations including outpatient, hospitalised, and oncology patients.248 The MNA-SF assesses both malnutrition and risk of malnutrition and has been used in two prospective studies of malnutrition among older adults in US EDs.242,244 Finally, although the SNAQ has been shown to be valid in the hospitalised patient setting, it classified too few patients as malnourished in a large multicentre study in the outpatient setting.249

For patients who screen positive for malnutrition, a comprehensive response requires at least four components:

- First, additional information should be obtained from the patient to identify modifiable factors contributing to the problem. Common modifiable risk factors for malnutrition among older adults include social factors such as food insecurity, depression, and social isolation, and clinical factors including dental problems and underlying medical problems.

- Second, based on this assessment, referrals to relevant clinical and community resources should be made to help patients address the underlying problem.

- Third, the treating provider and admitting team, for admitted patients, should be informed that the patient has screened positive for malnutrition. Providers may choose to request consults or referrals from specialised clinical staff such as a registered dietitian or nutritionist for further nutritional assessments and interventions.

- Fourth, the patient’s nutritional status should be communicated to their primary care provider to maintain continuity of care.

Of the above four components, the second is perhaps both the most important and the most complicated. The availability of community resources to address food insecurity and social isolation varies widely even within developed countries. Access to dental care and mental health services also varies widely. There is growing evidence that provision of home nutritional care lowers health care utilisation and areas with strong health care-community partnerships have lower nursing facility expenditures. Home-delivered meals programmes are an affordable investment in senior health: in the US the estimated annual costs of providing patients with daily meals for 250 days a year is $2,765, which is similar to the cost of one day in hospital.

Malnutrition is common among older adults presenting to the ED and can be rapidly identified with a brief questionnaire. Identifying malnourished older adults and linking these patients to resources has the potential to improve quality of life and health outcomes at a fraction of the cost of inpatient medical care. The primary challenge in achieving this goal is the development of relationships with local community-based services and identifying funding mechanisms to ensure timely and sustained access to these resources.

|

Resources: Nutrition in older people

|

Skin care and pressure injury

Pressure injuries are caused by unrelieved pressure (due to compression of soft tissue between a bony prominence and a hard surface), shear forces, friction, and a moist environment.250

Risk factors for pressure injuries include:

- Increasing age (for instance, patients older than 75 years of age have triple the incidence of pressure injures compared to younger patients)

- Inappropriate surfaces (stretchers, gurneys/trolleys, spinal boards, hard collars)251

- Impaired mobility due to trauma, delirium, sepsis, CCF, stroke, etc.

- Reduced skin perfusion due to hypotension

- Poor nutrition

- Incontinence

- Increased length of stay in ED

- Increased body temperature.

Pressure injury is an iatrogenic disease and adverse event; the majority are hospital acquired. A recent meta-analysis showed a pooled incidence of pressure injury in the ED of 6.3%.252 Even a brief stay in the ED or other parts of the hospital can lead to the development of pressure injury, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Pressure injuries lead to prolonged pain and discomfort, reduced quality of life (including psychological, functional, and social), increased risk of infection (including osteomyelitis, sepsis, endocarditis, meningitis, and necrotising fascitis) and increased mortality.

Pressure injuries increase hospital length of stay and considerable costs to the health system. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers increase the length of admission by an average of 5-8 days per pressure ulcer. The estimated annual cost to healthcare in the UK is £1.4-2.1 billion, and in the USA $11 billion. Costs to treat pressure ulcers are substantially higher than costs to provide pressure ulcer prevention, without including the cost of litigation.

Unfortunately, for the treating healthcare staff, there may be little evidence of tissue damage on initial examination and within the first few hours. That is because muscle tissue is the most susceptible to pressure injury, followed by subcutaneous fat and dermis.

Frontline clinicians are often unaware of some key facts, resulting in skin and pressure care being ignored. Pressure injury is common, and can start within two hours - or in as little as 30 minutes in high-risk patients (see above).

Pressure injury can be prevented by dedicated clinicians and nursing staff ensuring that, within two hours of presenting to ED, all older patients:

- Have a full-body skin check. Ensure that the patient is fully undressed, including socks, and is dressed in a hospital gown. A full body exam is fundamental. The patient is inspected for existing pressure ulcers, particularly the sacrum, coccyx and heels.

- Are moved from a barouche/trolley/gurney and onto a hospital bed with either a standard mattress or a specialised mattress. If on examination the patient has no existing pressure ulcers and is not in a higher risk group, a standard hospital mattress will be appropriate. However, if they have existing pressure ulcers or are in a higher risk group, a specialised mattress is recommended.

- Receive basic care in the ED which will include turning the patient every 2-3 hours for high risk patients, keeping the skin dry, providing hydration and nutrition, safe positioning (or avoidance) of tubing and masks to prevent friction/shearing, and prophylactic sacral and heel dressings if required.

Not only is moving an older patient to a hospital mattress within two hours of admission a significant way of reducing pressure injuries, but it is kind, more comfortable, and allows decent rest and sleep. The consequences of sleep deprivation are many, but its risk of delirium and impairment of the immune system is particularly important in this group of patients.

There are two main barriers in ED to delivering consistent pressure injury prevention. The first is the perceived need for a patient to be on a trolley in ED to facilitate imaging and resuscitation. In most case, patients requiring imaging or resuscitation procedures are managed just as easily on a ward-type bed, as often happens in ICU. The second is the extra workload on nursing staff filling in time consuming pressure injury paperwork. To this end, if the patient has had a full-body skin check when they are undressed and were placed on an appropriate mattress within two hours of admission to ED, the risk assessment tools and associated paperwork are of secondary importance for ED staff.

|

Resources: Pressure injury |

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is characterised by bradykinesia (slowness), hypertonia (stiffness), postural instability, and tremor.

It has a wide range of aetiologies, including idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, vascular disease, medication-induced, and Parkinson’s plus disorders such as progressive supranuclear palsy, multi-system atrophy and Lewy body dementia. Parkinsonism is very common in older people (there are prevalence estimates of 15% in people 65 to 74 years of age, 30% for those 75 to 84, and 52% for those >85) and is associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of death.253 Complications of Parkinsonism, including falls, fractures, delirium, pneumonia, and orthostatic hypotension are a frequent cause of presentations to the ED.254

Clinicians should be vigilant for undiagnosed patients presenting to urgent care settings, as they will likely benefit from referral to a movement disorders specialist. In particular, patients with falls should be carefully examined for any of the characteristic signs detailed above. In patients with established diagnoses of parkinsonism presenting with falls, it is important to consider the specific factors that have contributed to the fall, including posture, freezing of gait, cognitive impairment, medication-induced risk-taking behaviours and orthostatic hypotension. Such patients are likely to benefit from referral back to their movement disorders specialist rather than to generic falls clinics. It is also important to remember that patients may have causes for their fall completely unrelated to their Parkinsonism, and these should not be forgotten.

Patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease are highly dependent on their medications, and these should be given at the correct dose, by the usual route, and on time. Provision should therefore be made for rapid availability of Parkinson’s medications in the urgent care setting, and consideration should be given to allowing patients to self-medicate. Where patients cannot take their usual medications orally, due to being too drowsy or nil by mouth, urgent consideration should be given to insertion of a nasogastric tube for medications or switching to the transdermal patch, Rotigotine. It is important to be aware that Rotigotine has a different mode of action and side effect profile to levodopa and cannot therefore be considered equivalent. Rotigotine also does not have a specific licence for use in this situation, but is far preferable to patients being left un-medicated as this will cause worsening of symptoms with the potential to cause aspiration pneumonia and in-hospital falls. It is also very important to be aware that un-medicated patients can appear to be dying when they are not. Withdrawal of anti-Parkinsonian medications can also trigger the life-threatening emergency, Neurological Malignant Syndrome (NMS). This is characterised by the tetrad of altered mental status, rigidity, hyperthermia and dysautonomia and is confirmed in the presence of a raised CK. Leucocytosis and mild elevation of LDH and liver enzymes is also common. The non-specific features of NMS mean that it can be under-recognised. However, clinicians should be vigilant as the condition has a high mortality and patients may require critical care input.

Patients with Parkinsonism should not be given dopamine depleting medications, including antipsychotics such as Haloperidol, and anti-emetics such as Metoclopramide. If rapid tranquilisation of a patient with Parkinsonism is needed, then benzodiazepines are the drugs of choice. Cyclizine and ondansetron are suitable alternative anti-emetics.

When considering how to make your ED more Parkinsonism friendly involve Parkinson’s disease nurse specialists, movement disorders neurologists and geriatricians, pharmacists, therapists, and patient groups. Consider having a specific flag or alert system for when patients with Parkinsonism are admitted. Encourage staff to undertake specific training in Parkinsonism to raise awareness; there are excellent learning resources at Parkinson's UK, and elearning modules at The Association for Elderly Medicine Education (AEME). Ensure that your urgent care setting has rapid and consistent access to Parkinson’s medications. When it is necessary to convert medications to either a regime for NG tube delivery, or a transdermal patch, use an approved online calculator such as the OPTIMAL calculator, or refer to published guidelines e.g. NICE.

Abuse and safeguarding

Elder abuse is defined as action or negligence against a vulnerable older adult, causing harm or risk of harm, and committed by a person in a relationship with an expectation of trust.

Assessment by urgent care providers may be the only time a victimised older adult leaves their home or the institution where they live. Existing research suggests that elder abuse victims are less likely to receive routine care from a primary outpatient provider and more commonly seek urgent care for acute injury or illness, though Urgent Care providers very seldom identify or report elder abuse. This is likely due to inadequate education about the importance of elder abuse or training in identifying signs of abuse, uncertainty about appropriate next steps after identification, and concerns about effectiveness of interventions.

Urgent care providers should provide additional education/training to clinicians, consider screening all older adults for abuse and develop protocols for elder abuse identification and response. Training staff on elder abuse identification and next steps to take if concerned about mistreatment is essential. Many elder abuse victims present with problems unrelated to abuse, and cases may be subtle, so a knowledge of red flags and a high index of suspicion in necessary. To facilitate improved identification, providers need to be aware of the risk factors (see Table 2), observations from older adult / caregiver interaction that should raise concern (see Table 3), indicators from the medical history (see Table 4) and suspicious physical signs (see Table 5).

|

For becoming a victim |

For becoming a perpetrator |

|

|

|

|

|

Physical abuse |

Sexual abuse |

Neglect |

|

|

|

If a provider suspects or confirms elder abuse, they should:

- Treat acute medical and psychological issues

- Ensure patient safety, and

- Report to the authorities.

To ensure safety, alternate living arrangements may need to be arranged for the patient, and hospital admission should be considered if immediate danger exists. If the patient refuses intervention, a provider must determine whether the patient has the capacity to make this decision. Providers should report concerns about elder abuse to authorities, including the police and/or adult protective services as appropriate. In some countries, medical providers are mandatory reporters for elder abuse, and providers should be aware of relevant local laws. The medical chart may be used for investigation and prosecution, and quality of the documentation can significantly impact justice and protection for a victim.

Multiple screening tools exist that may be used: the Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (EASI) is a short tool validated for cognitively-intact patients in ambulatory care; the ED Senior AID (Abuse Identification) tool is a promising ED-specific screening tool recently developed and currently undergoing validation. An alternative approach is a multi-step process including a brief initial screen for all older adults followed by a longer, more comprehensive screen if concern is identified.

|

Resources: Abuse of older people |

End of life care

Due to the technical evolution in medicine, many treatments are available to prolong life or postpone death. The appropriateness of those technical interventions and medical treatments can be questioned, especially in people with serious underlying chronic illness or severe frailty nearing the end of life.

The appropriateness of a medical treatment is defined by the reversibility of the acute event, the feasibility of the intervention, life-expectancy, and the match between the expected benefits and the care goals of the older person. To define these care goals the values and needs of the patient him/herself should be or have been explored. Advance care planning as a regular process following or triggered by acute events is important to discuss the wishes and needs of the person and to come to shared decision making.

The reversibility of the event often defines the outcome. Treating an acute event that is easily reversible (e.g. urinary tract infection) will cause less discussion about appropriateness compared to acute events that are known to have less favourable outcome, such as shock due to ischemic bowel.

The feasibility of the intervention is often linked to the reversibility of the event. Easily reversible events will often need less intensive interventions.

Defining prognosis is an important step in defining the moment to start talking about end of life care; this is typically where the prognosis is 6-12 months. One of the most important prognostic factors for outcome in the older person is the underlying functional capacity, which can be captured as frailty, for example using the Clinical Frailty Scale. Treating an acute exacerbation or event in a patient with a chronic underlying condition for which no therapeutic options are left will never affect the severity of the underlying condition or its effect on the person’s quality of life and life expectancy. On the other hand, hesitating and delaying a treatment for an acute event can negatively affect the outcome, especially in older people with frailty.

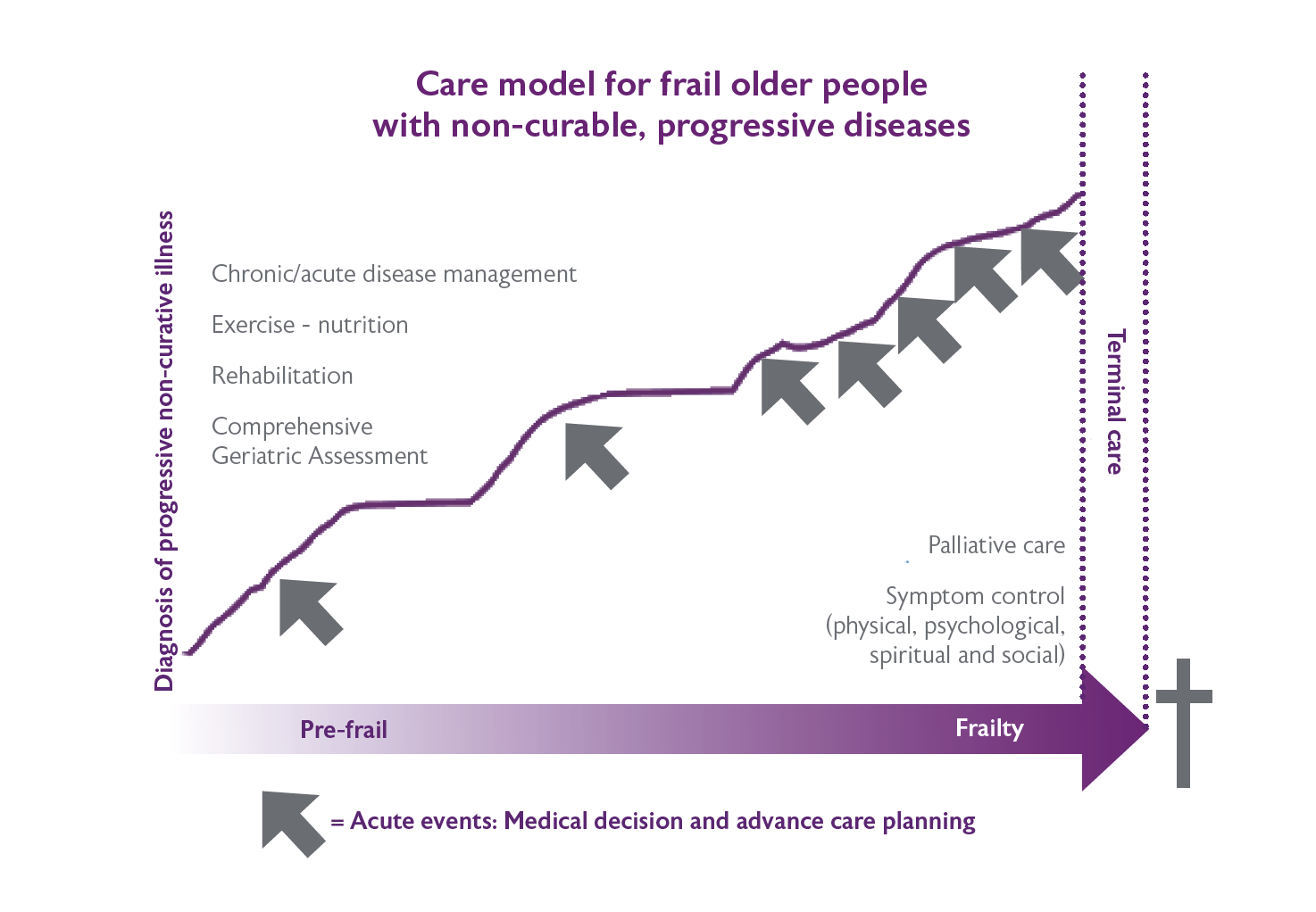

Many tools are available to help clinicians to estimate the prognosis. On a population level these tools have proven to be reasonably reliable with AUC of about 0.8 for most. However, on an individual level, many unpredictable factors seems to interfere, meaning that an accurate prognostication on an individual level is rather difficult. Examples include the Multidimensional Prognostic Index, e-prognosis and the Supportive & Palliative Care Indicators tool. For many diseases, there are disease specific tools that help to estimate life expectancy. Figure 5 is based on the WHO model of integrated care for the older person, and could be useful to guide health care professionals in treating patients with progressive non-curable illness.

A second important pillar in decision-making are the needs and preferences of the patient themselves. If the individual has the capacity, even if there is an advance statement, an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) or an appointed personal welfare Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA), the health care provider should always discuss the possible treatments and the way they will support the goals of care with the patient. If medical treatments do not support the goals of care, they should be considered as disproportionate care and withheld or withdrawn. If the patient lacks capacity, the health care provider should check for the presence of an advance statement, an ADRT or an LPA for personal welfare. If one of these are present, the health care provider should check if the treatment is in accordance with the ADRT or should discuss with the LPA if the treatment is in accordance with the preferences of the patient. If the person lack capacity and they have no documented wishes, the health care provider should try to find out the person’s views (i.e. wishes, preferences, beliefs and values) by consulting others (within the limits of confidentiality and regional laws).

After gathering information, the health care provider should weigh up all of these factors in order to work out the person’s best interests. If no one is available in case of an emergency, the health care provider should act in the patient’s best interest. If possible, depending on the urgency of the decision, this decision should be taken in consensus between different team members.

The correct recognition and management of the last days of life in the urgent care setting is very important for the patient and their family as this will influence the family’s bereavement and the way they will cope with the loss of their loved one. Frequent symptoms in the last hours of life are pain, restlessness, agitation and terminal respiratory secretions (‘death rattle’). Adequate recognition and treatment of these symptoms should start in the urgent care setting.

During the last days of life, focus is put on relief of symptoms. Pain and shortness of breath can be mostly controlled by continuous delivered opioids intravenously or subcutaneously. In opioid naïve patients, Morphine should be started in low doses (10 to 20mg intravenously over 24 hours after a bolus of 2mg in patients with severe pain). For previous opioid users, adequate doses and opioid should be chosen depending on the already used opioid. Death rattle is caused by respiratory secretions which cannot be cleared anymore. This noisy breathing may be more distressing for the family than for the patient. Giving families information about the origin of the death rattle is the first step. There is some controversy in the literature about the evidence for the use of anticholinergic drug at the end of life. Anticholinergic medication as hyoscine hydrobromide (0.5mg/4h SC, IM) or glycopyrronium (200 to 400µg given every 4 to 6 hours SC,IM) may be considered if the aim is to diminish the production of respiratory secretions. These drugs can be added to the syringe driver. For patients with terminal restlessness, the use of psychotropic medications as midazolam and if hallucinations, the use of haloperidol or clotiapine can be considered. These can be also delivered subcutaneously. Enteral or parenteral food or fluids have no proven benefit on symptoms of dehydration or on life prolongation and can possibly harm the dying patient. The pros and cons of their use should be discussed with the next of kin.

For most people who are dying, this approach will enable to manage the symptoms causing discomfort. In complex cases, urgent advice of palliative care team could be considered. More in-depth information on the management during the last days of life can be found in the resources box below.

|

Resources: End of life care |

Ethical issues

The foundation principles of ethical care for older people are the same as for any other human beings.

- Respect for patient autonomy

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

However, it is the application of these principles in the care of older people where there are challenges. Older age is commonly associated with degrees of physical and cognitive impairment and with these come increasing dependence and vulnerability. Consequently, although usually with good intentions, there is a tendency for healthcare professionals to be paternalistic towards older people – to interact with them as a father might with his son. Respect for people's autonomy is important to bring about the best outcome for the patient. However, it is also immensely fulfilling for the patient to know they have been listened to, been heard and their views are respected.

The abilities of older people to articulate their true autonomous wishes might deteriorate with cognitive and physical impairment. Consenting to a particular management plan is an expression of autonomy and usually requires adequate hearing, understanding the pros and cons of the options, deliberation, and expression of a decision which is free from coercive influences. It is a responsibility of care providers to maximise the patient’s abilities in this regard. Often, impairment in these abilities might be transient and a decision can wait until they have improved, or until more certainty about the patient’s true autonomous wishes is available. However, if the context requires a decision more urgently, and particularly when the patient is refusing care which would seem to be in their best interests, then the patient’s autonomy can be explored further.

A true autonomous decision has a number of foundations but a pragmatic distillation of the key components can be explored by asking these questions:

- Do they know enough? (have they been sufficiently informed?)

- Can they think enough? (is their cognitive ability or ‘mental capacity’ adequate?)

- Are they free enough? (are they free from coercive influences?)

If the answer to each of these is ‘yes’, then the decision they express should be respected. However, if the answer to any of these is ‘no’ then the care provider should seek to determine what their true autonomous wishes would be.

There are tools and guidelines for assessing mental capacity (the General Medical Council (UK) Mental Capacity tool is an excellent resource), but the key indicators that an expressed decision is from someone with adequate capacity are understanding and reason. Understanding can be explored by asking the patient to explain back what they understand about the management options and their pros and cons. Reason can be explored by asking why they have come to the decision they have. Understanding the patient’s reasoning also allows potential modification of plans to mitigate concerns they might have.

If there are good clinical reasons to provide management (beneficence and non-maleficence), the patient cannot express a view or it is believed the view they express is not a true autonomous one (usually because of inadequate mental capacity) and there is good reason to believe their true autonomous wishes, if they were able to express them, would be to consent to the management, then management should proceed. Indeed, doing so, in this context, is respecting their true autonomous wishes.

Determining what their true autonomous wishes would be, were they able to express them, is greatly informed by information conveyed in previous conversations or documentation, and from the views of those who know the patient well. Ideally, the patient’s true autonomous wishes are documented in an Advance Care Plan (or similar), completed when the patient was able to express their true autonomy, and relevant to the circumstances in which they now find themselves. Respecting the true autonomous wishes of the patient is the foundation for ethical care and in most jurisdictions this model of ‘presumption of consent’ has legal backing. However, in some jurisdictions, proxy consent from a relative might have some precedence, particularly when a patient has an active enduring power of attorney for health matters. It behoves the health professional to understand their own legal context.

In this section, among the principles of Beauchamp and Childress, autonomy has had the most focus. However, the principles of beneficence (helping) and non-maleficence (not harming) have been considered, and have particular relevance for older people. Respect for their true autonomous wishes and for their dignity demand careful consideration about when interventions are potentially doing more harm than good and would not be the true autonomous wish of the patient.